24/7/24

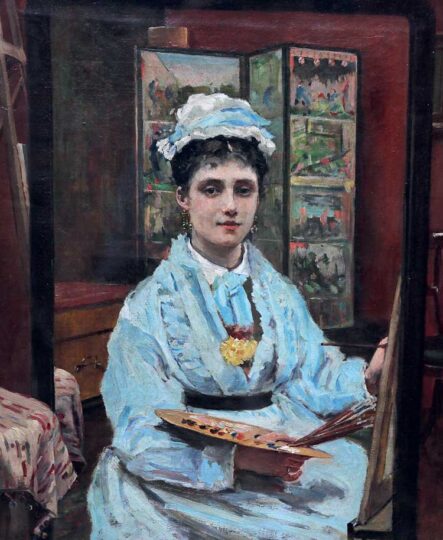

Now You See Us. Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920

Tate Britain, London

16 May – 13 October 2024

A young woman, dressed in black with a bonnet and long shawl, accompanied by a small boy, stands waiting, eyes down, fidgeting nervously with a piece of string, while a portly older man looks haughtily at a painting she has brought into his shop. Behind her, two men in top hats peer superciliously at her over the top of a picture of a ballet dancer. This well-known painting, Nameless and Friendless (1857) by Emily Mary Osborn, was, according to the feminist art historians Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin, “meant to be ‘read’ rather than merely looked at, to arouse moral feeling rather than simple appreciation of its visual qualities”. The plight of women was one of Osborn’s principal themes, and sentimental genre scenes, emphasising the blameless domestic lives led by middle-class women – the so-called “Angel in the House” – were popular with the Victorians, but to show a professional female artist in distress like this was unusual to say the least. The painting has, perhaps unsurprisingly, been misinterpreted by (male) critics as, for example, “a gentlewoman reduced to depending upon her brother’s art”, and, indeed, Osborn’s own career was far removed from that of her protagonist, since, the daughter of a priest, she was encouraged to be an artist by her family and was supported by wealthy patrons, including Queen Victoria. Osborn used this position of power, however, to help improve the lives of those like her protagonist here and in other works. She was also a member of the Society of Female Artists, established in 1855, two years before she made this work, to help women overcome the difficulties they faced in exhibiting and selling their work. This painting, and this artist, offer a good introduction to questions on the lot and subsequent battles of female artists throughout art history – if, indeed, this disconsonant concept of the “woman artist” even exists.

Read my full review here