08/06/25

‘Cut. You say I. And I bleed’: Words as Wounds in the Work of Brooke Leigh

Cut. You say I. And I bleed. I am outside … I no longer have what I once had … You’re not there any more … I still want to have … To hold on to what is going to disappear … The body, here. Separate …[1]

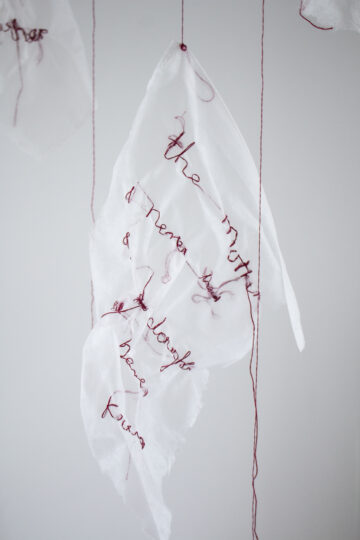

Like cobwebs fluttering in the breeze, Things Felt But Never Heard hangs, as if suspended from thin air (its burgundy threads attach higher up to fishing wire), words clinging to the evanescent material, full of sadness and despair, so tightly that in places it is scrunched up, puckering the text, taut, breathing in anxiety, forgetting to breathe out.

Installation view of five textile drawings from the ongoing series Things Felt, But Never Heard, 2025. Cotton thread on polyester shoe dust covers. © Brooke Leigh.

Written on the body is a secret code only visible in certain lights: the accumulations of a lifetime gather there. In places the palimpsest is so heavily worked that the letters feel like Braille. I like to keep my body rolled up away from prying eyes, never unfold too much, or tell the whole story.[2]

In Brooke Leigh’s current work, there is no body, yet the body remains omnipresent. The feelings evoked by these minimally expressed thoughts and emotions weigh heavily, dragging their gossamer conveyers earthwards, countering their buoyant force.

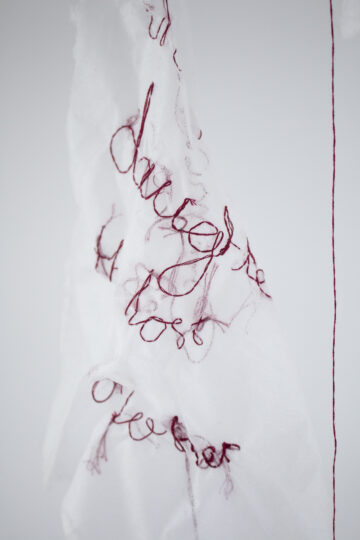

The words cry out in layers, clause upon clause: And even…; but… They literally shape the material on to which they are sewn, crinkling and crumpling it like an autumn leaf: fragility; diaphaneity; delicacy. Hovering; floating; gasping. Exhaling as the umbilical cord is cut, separating the one from the m/Other, cut adrift, push-pull, forever entangled, alone. The mother wound is raw. It seeps and creeps deep into our core.[3]

daughter and mother … imperfectly separated, they cleaved one to the other.[4]

Brooke Leigh, The mother I never had, the daughter she never knew, 2025. From the ongoing series Things Felt, But Never Heard. Cotton thread on polyester shoe dust cover. © Brooke Leigh.

And yet these rejected conceptualisations are neither bitter nor venomous; they strike a balance or dialectic: the subject (I) and the m/Other. I was the strength you never had; The mother I never had the daughter she never knew.

Blood flows from one body to the other, from one epoch to another.[5]

In her MFA thesis, Leigh speaks of ‘a background of emotional abuse, a compromised sense of self, and a long-standing feeling of helplessness,’[6] and with a lack of stable identity, one flails and grasps at each and every feeling and thought, ramping up their intensity with a violent passion: overfeeling, overthinking, overcompensating and overbeing. Getting nowhere. Leigh writes of ‘affirm[ing] my existence – reasserting a sense of self’.[7] Re-asserting, repeating. In places the letters appear to have been double or triple-stitched. The French philosopher Henri Bergson notes, in his essay The Intensity of Psychic States: ‘[W]e reach the sensation of higher intensity only on condition of having first passed through the less intense stages of the same sensation.’[8] Leigh’s work accumulates, the two dimensional becomes three, her feelings are sculpturally embodied, and their intensity is sorely felt: the space around the installation is heavily charged, laden; anyone who enters becomes trapped in flight mode. The immediacy of the anxiety is breathtaking – or, rather, breathstopping.

Where does a feeling go once it has been felt? Where does hurt and pain go? The body doesn’t easily let go. The wound remains open. Unprocessed shame and fear, anger and hurt, become stuck, until one day the balance is tipped. Processing these emotions involves acknowledging, accepting, and allowing ourselves to feel them. By speaking her feelings, writing them out loud, drawing them, as the artist Chiharu Shiota describes, ‘in the air’,[9] Leigh articulates herself. What is key is not the rejection of the m/Other, but the assertion of self. The found daughter the lost mother. In Angst, the French feminist writer Hélène Cixous suggests that this will be a language in which ‘she’ will also have the status of subject: ‘a sentence with room for me in it’.[10] Elsewhere, she devotes an entire essay to pleading with women to write: ‘Write yourself. Your body must be heard. Only then will the immense resources of the unconscious spring forth.’[11] Where does a word go once it has been uttered? Does it still exist? Leigh’s words flutter in the breeze, ‘tracing day after day our own text in letters of blood’.[12] Tracing the ephemeral, she embodies it; tracing the physical, she makes it ethereal.

Brooke Leigh, The found daughter, the lost mother, 2025. From the ongoing series Things Felt, But Never Heard. Cotton thread on polyester shoe dust cover. © Brooke Leigh.

In her large-scale installation Beyond Memory, that was part of the group exhibition And Berlin Will Always Need You at the Gropius Bau, Shiota weaves together a network of white thread with historical documents from the museum. ‘The yarn creates tension like a human relationship – it tangles, it interacts, it creates voids and evokes memories. Something happens when you see it.’[13] While conversely Leigh has material holding thread, rather than thread holding documents, the feel is the same. Her words are like traces of presence, of being, of self. Her words are wounds. The French philosopher Jacques Derrida refers to glimpsing the radical absence, the trace, or the true representation of things in the space in between repetitions. The singular condition that allows us to represent the world to ourselves at all is this trace or void between word and thing; our experience of presence is mediated by an absence that we can never experience as such.[14] Both of these conditions capture Leigh’s work perfectly: Things Felt But Never Heard are physical traces of ephemeral words; their radical absence embodies the intense presence of their feeling. Words. Traces. Wounds. The mother wound.

© Anna McNay, June 2025

[1] Hélène Cixous, Angst, Paris: des femmes, 1977, translated by Jo Levy, London: John Calder and New York: Riverrun Press, 1985, page 9, cited in Susan Sellers, Language and Sexual Difference: Feminist Writing in France, London: MacMillan, 1991, page 62.

[2] Jeanette Winterson, Written on the Body, London: Vintage, 1992, blurb.

[3] It should be noted that Leigh does not see the burgundy as representative of blood, but, following the artist and writer Monica Sjöö (monicasjoo.co.uk/2014/03/30/triple-goddess-at-pentre-ifan-cromlech-the-womb-of-cerridwen/), I am very specifically distinguishing between the life-giving umbilical and menstrual liquid drunk from Cerridwen’s cauldron (symbolic of her womb and later to become the chalice of the Holy Grail) in Celtic and pre-Celtic times and the red blood of a crucified man which replaced this later on.

It may also be noted that Leigh has now begun a second series of similar drawings, this time using a navy thread, which is ‘focused on broader experiences of anxiety, distress and despair,’ as opposed to the burgundy Things Felt But Never Heard, which ‘relates to my childhood and complex maternal relationships’ (personal exchange).

[4] Chantal Chawaf, L’Intérieur des heures, Paris: des femmes, 1987, page 70, cited in Sellers, op cit, page 65.

[5] Chantal Chawaf, Le Soleil et la terre, Paris: Jean Jacques Pauvert, 1977, page 8, cited in Sellers, ibid, page 68.

[6] Brooke Leigh, Drawn-Out: Trace and Catharsis, MFA thesis, University of Sydney, December 2017, page 27.

[7] ibid, page 26.

[8] Henri Bergson, The Intensity of Psychic States, in Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness, translated by FL Pogson, London: Allen & Unwin, 1910, pages 1-74, pages 5-6, cited in ibid, page 61.

[9] Inga Nelli, Chiharu Shiota: Conversations, in Coeur et Art, 2019, coeuretart.com/conversations-chiharu-shiota/.

[10] Hélène Cixous, op cit, cited in Sellers, op cit, page 27.

[11] Hélène Cixous, The Laugh of the Medusa, in Signs, Vol 1, No 4, summer 1976, pages 875-893, page 880.

[12] Marie Cardinal, Autrement dit, with Annie Leclerc, Paris: Editions Grasset, 1977, page 222, cited in Sellers, op cit, page 27.

[13] Nelli, op cit.

[14] John Phillips, Introduction to Derrida: Presence and Absence, course notes, National University of Singapore, 2013.