I have images I love wholly aesthetically, in which I would like to be lost, and at which I could sit and look for hours; then, as a writer, I have images I love because of their complexity or context and the different angles they offer for exploration or the stories they tell about their creation. This – Road from Abiquiú (1964-68) by Georgia O’Keeffe – is one of the latter.

O’Keeffe is part of the story of modernist photography whether she likes it or not. She was married to Alfred Stieglitz, who took more than 300 photographic portraits of her (some of an explicitly erotic nature), and she was friends with the likes of Paul Strand and Edward Steichen. She was clear about her artistic goal from the outset, however, stating: ‘I want to be a painter, just a painter.’ Nevertheless, she also said: ‘Art must be a unity of expression so complete that the medium becomes unimportant – only noted or remembered as an afterthought.’ Accordingly, the photographs that O’Keeffe took in her later life (from the mid-1950s onwards) overlap significantly with her paintings in terms of (often abstracted, if not abstract) form and composition, light and shadow.

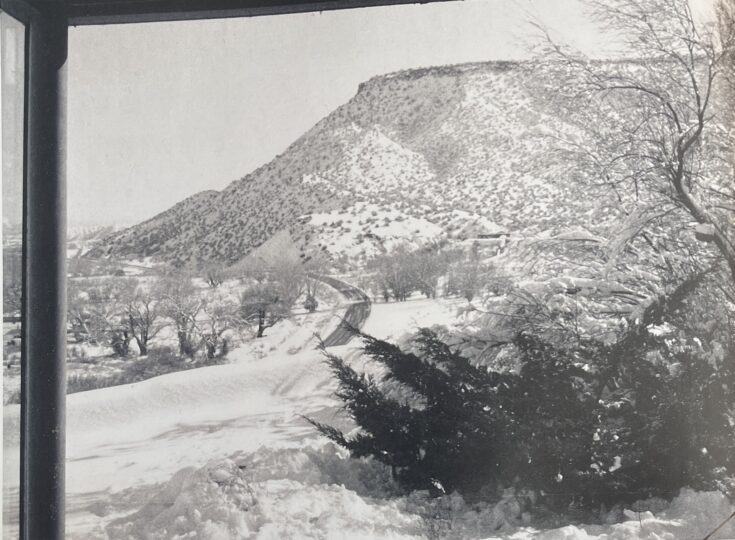

Road from Abiquiú (1964-68) is one of seven photographs of the mesa and road outside O’Keeffe’s east (bedroom) window, tracking the view at different times of year (here the hillside appears bare through the thick swathes of snow). This image is especially curious, however, since, at first glance, it seems rather sloppy, with part of the window frame crookedly appearing at the edge of the composition – something to best be cropped out? Comparison with No. 24 Special/ No. 24 (1916-17) – a painting made half a century earlier – however, would suggest not, since it likewise frames the (different) mountainous bulge with a window frame – a frame within a frame. This is an ancient device, and O’Keeffe exploits it, in both the painting and the photograph, to undermine the perceived three-dimensionality of the image by rendering the view outside the window as just another scene to be framed, another two-dimensional picture.

Additionally, in the very centre of the image, a comma-like stretch of Highway 84, which reached past O’Keeffe’s home and wound around the mesa towards Espanola and Santa Fe, appears like a brushstroke, punctuating the composition. ‘The road fascinates me with its ups and downs and finally its wide sweep,’ O’Keeffe wrote. ‘I had made two or three snaps of it with a camera. For one of them I turned the camera at a sharp angle to get all the road. It was accidental that I made the road seem to stand up in the air, but it amused me and I began drawing and painting it as a new shape.’ While this landscape-format image does not show the road as fully upright as her vertically composed one does, there is still a sense that the road is an autonomous body, sketched as a sinuous afterthought on to the flat picture, in the manner of the Japanese brushwork she had experimented with in the 1910s and the ribbons of rivers she sketched from airplanes in the 1950s.

Apparently Stieglitz used to say that O’Keeffe knew less about photography than anyone else he knew, and, indeed, it was only after her husband’s death that she began seriously making photographs of her own. Even then, however, she never mastered her Leica 35mm camera or her Polaroid Land Camera, instead relying on her friend, the photographer Todd Webb, to set the exposure controls, or using a set of crib notes, reading, in part: ‘Check to see if sprocket engages holes in film — Pull spool up & down — shake spools till it does.’ Unlike professional photographers, O’Keeffe was never concerned with creating perfect photographic prints either; her interest lay in the image itself rather than the final print. She used her instant camera, printed her work at drugstores, or asked Webb to create test prints or enlarged contact sheets of her pictures, which she pointedly called ‘snaps’, not ‘photographs’. Her prints also show evidence of frequent handling, with ink and paint stains, fingerprints and scratches in the emulsion. The mark on the bottom-righthand corner of this print suggests it may, at some point, have been taped to a surface.

What is most fascinating about the 400-plus photographs taken by O’Keeffe is her constant act of reframing. In any given ‘series’, she would compose and recompose, looking upon her environment as an array of shapes and forms. Moving from left to right, angling the camera from high to low, and turning it both vertically and horizontally, she reorganised these shapes within the picture frame as she experimented with formal arrangements. This device is quite distinct from those of her contemporary photographers, who would crop, as a method of emphasis, during the darkroom process. O’Keeffe’s ‘cropping’ took place in her mind’s eye and the camera’s viewfinder. Her vision of nature was both shaped by and painted with light.

Also published at On Landscape