15/04/20

In dialogue with Anna McNay

An unexpected meeting, a coincidence that unites us for a few moments: the perfect environment to meet with this warm woman and begin our conversation. They say that with people who are thoughtful, empathetic, understanding, and at home with their soul, you often have the feeling of having known one other for a long time. Even if it is scientifically proven that the language you speak influences your thinking, it seems that the soul speaks one and the same universal language.

An interview about art with Anna McNay, an art writer and curator with an extensive background in the art world, coloured by her personal spirit.

(Written by Felicia Acsinte, art curator from Romania)

Felicia Acsinte: Can you tell me more about yourself? About your passion for art history?

Anna McNay: I came to be an art writer, editor and curator purely by accident. My first career was in academia, as a research and teaching fellow in linguistics at, first, the University of Oxford, and, latterly, the Humboldt University in Berlin. I specialised in syntax and information structure – so word order and meaning – and it was all highly theoretical, or, as a colleague described it, ‘brain games’. Since the age of 13, I’ve been plagued with numerous chronic illnesses, including Hodgkin Lymphoma, and myriad secondary illnesses and late effects of the treatments I received. I fell ill while in Berlin and had to take six years out of my life to recover. I knew I couldn’t return to my academic career and didn’t really know where to turn. As a child, the first career I ever wanted was that of an artist, and there’s a fabulous photograph of me, aged about five, in a Mickey Mouse smock, with my easel and paintbrush. I grew up with art and a house full of art books, as it is my Dad’s passion as well. Throughout those six years of ‘recovery time’, I took numerous courses in art history, and I also visited a lot of exhibitions. I was – and am – a huge fan of Tracey Emin, and also had a happy childhood memory associated with Margate, on the south coast of England, where she was from. So, when I saw an advert for a research intern, for an exhibition at Turner Contemporary, a new gallery that was being built in Margate, I applied – after all, research was my background. Amazingly, I got the role, and this was the beginning of a new chapter in my life! I remember going to see my parents and saying: ‘Do you think there might be jobs out there relating to art?’ I’d really been so blinkered down the academic route before that. The team at Turner Contemporary was really supportive and suggested I should do an MA in the History of Art, if I was serious about wanting to work in this field, so I applied to Birkbeck College at the University of London, where you are able to study part-time in the evenings. Having been in a position where I was teaching post-graduates, I didn’t want to return to being one full-time myself. During the two years of studying, I did numerous other things: moved to London, took a course in curating, began seriously attending exhibitions and networking with artists and gallerists, and also writing reviews. I was really lucky in that I met the creative director of Studio International at an event, and he asked me to write something for them. They liked it and kept me on as a contributor. Through meeting people, I got further opportunities, and began to write essays for galleries and artists, carry out interviews, write profiles… I got regular gigs with a number of art and photography magazines. And when Studio International decided to try doing filmed interviews, I was the ‘guinea pig’ interviewer. Luckily it took off! I became Arts Editor for DIVA magazine and Deputy Editor for State/F22, as well as contributing widely elsewhere. I also began to judge competitions and host panels and in conversations with artists. By the time I’d finished my studies, I was really busy. In March 2017, I took on a full-time role as assistant editor at Art Quarterly, the membership magazine of a national arts fundraising charity, Art Fund. I learned a lot, as I had to manage the production and image research and licensing side of things as well as commissioning, writing and editing. This January, again due to health reasons, I returned to full-time freelancing. Luckily, I had continued this work throughout, so I have been able to build it back up fairly easily – not taking the knock-on effects of coronavirus into account… I love my work as I basically get to see art, speak to artists, and write about it all. When I am commissioned for a feature or essay, I get to research and learn lots, which is my real passion still – that and editing (because my pernickety inner grammar fiend gets to insert lots of commas!). People always ask me who my favourite artists are, or my favourite periods. I usually say it depends on the day! But, as I said, Tracey Emin really strikes a chord, but so do the German Expressionists, French fin-de-siècle artists, Austrian Secession artists, Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollock, and more recent artists, such as Howard Hodgkin and Albert Irvin. But that is a far from exhaustive list.

You are part of a society that is much more deeply connected and open to Western artistic discourse. In the broader global context, what is art in our days?

For me, art has to function on an aesthetic level first and foremost. It should affect the viewer viscerally. Despite my making a living writing about art, I think that any art that requires words to make it accessible, or for someone to be able to respond to it, has failed as art. Unfortunately, the legacy of and fondness for conceptual art lives on, and so many students still churn out ‘ideas’ rather than ‘art’. The ideas, in and of themselves, might be quite brilliant, but unless they can be translated into something, like I say, aesthetic and viscerally impactful, then, to me, that too is just ‘brain games’.

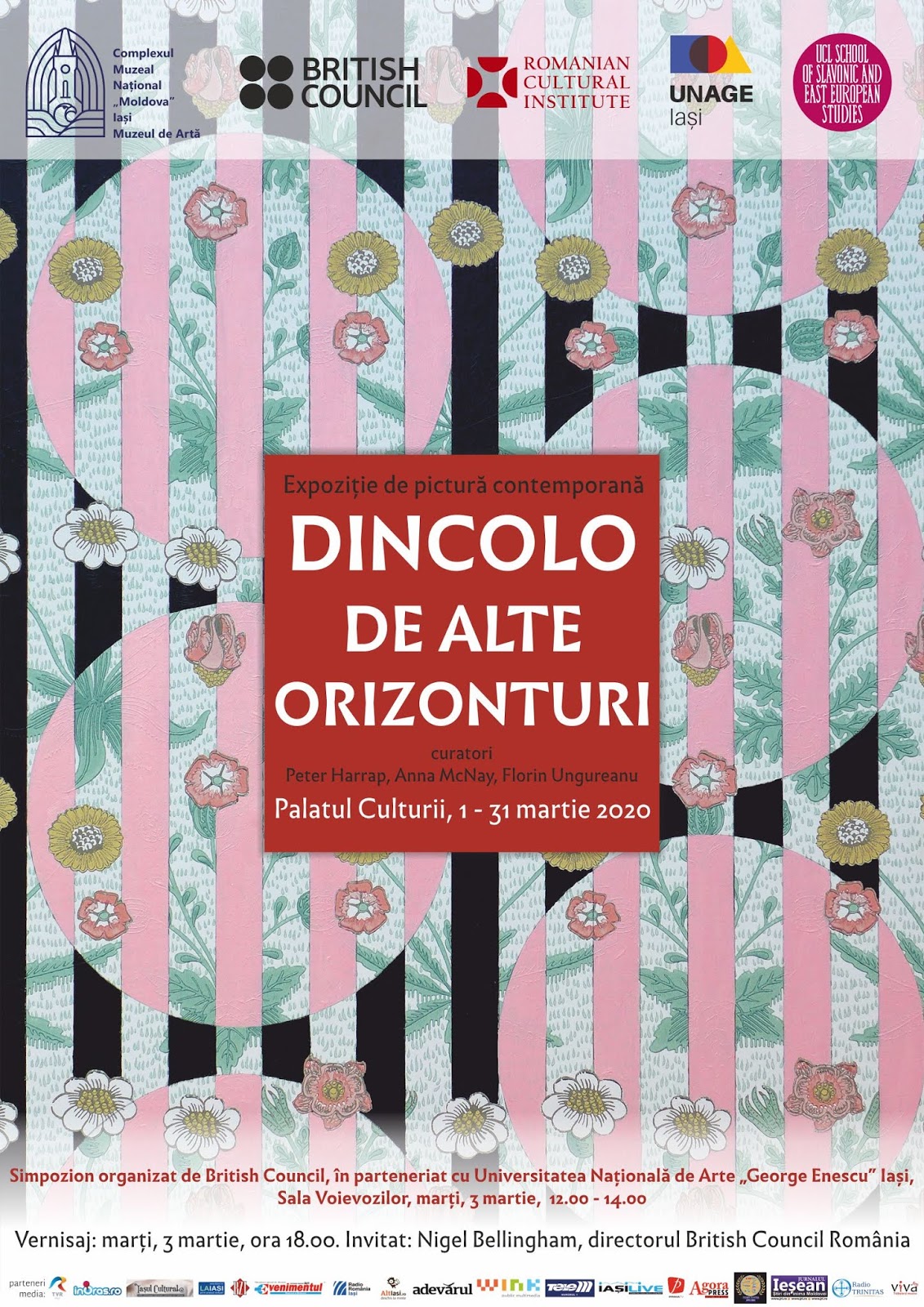

Anna, you recently were in Romania, more exactly in Iași, where you curated the exhibition Beyond Other Horizons, an exhibition of works on paper by 40 Romanian artists and 40 British artists. How would you describe the exhibition and accompanying events?

I was one of three curators for this exhibition, alongside Peter Harrap, also based here in the UK, and Florin Ungureanu, who works in the Palace of Culture in Iași, where the exhibition was on show. The original idea grew out of another exhibition I co-curated in Gdansk, Poland, last year, with works by artists belonging to a group here in the UK called Contemporary British Painting. The group was founded in 2013 by Simon Carter and Robert Priseman, both painters who are hugely passionate about painting, and who wanted to create more opportunities for painters to exhibit, in an art world dominated by new media. Peter approached me and Robert, but, as things developed, Robert stepped back, Peter introduced the idea of curating the exhibition around the ideas of the Romanian poet Paul Celan, and, more specifically, his poem Mapesbury Road, written while in London, and we invited new artists who don’t belong to the CBP group to also participate. Florin largely suggested the artists for the Romanian half. And, due to funding and transport issues, we ultimately decided to make the exhibition one comprising works on paper.

The exhibition opened with a private view, and, on the same day, a British Council symposium, with papers looking at the works and artists included, and the three key curatorial themes, drawn from Celan’s poem, and according to which the works had been hung: language, walking, and otherness/the surreal. About half of the UK artists came over for this, and thankfully we all made it home, just before the museum was shut down as a precaution against coronavirus.

Can you make a comparison between the London artistic and cultural atmosphere and that which you have seen in Iași? What is the difference between the two?

I didn’t really have chance to see much of the art scene in Iași, so it’s hard to say. Although, from what the artists who came with me went to visit, and from what I myself was taken to see, there didn’t seem to be any/many contemporary art galleries in Iași – at least, none that were obvious or easy to find. I think, on the other hand, London has so many that it’s hard to walk even a couple of streets without seeing contemporary art of some form or other. The cultural offerings in Iași seemed to be much more based around historical museum artefacts, older art, and religious art, in the churches and associated museums. Of course, this might not be the case at all – it could just be that I didn’t have long enough to explore, and also didn’t have chance to chat much with any of the Romanian artists.

Can you make a recommendation for artists and Romanian curators? What they must to do to be of a higher level?

Again, not having seen any contemporary art exhibitions, it is hard to compare and offer advice, but I’d say to be open to what is happening internationally; to encourage art students and give them opportunities to exhibit and to sell; but also to be discerning – don’t just put everything on display: select, curate, find ways to draw out themes, bring out the best in the work and the artists, and interest audiences. It doesn’t have to be academic, it doesn’t have to be weighty – just find ways to engage. I don’t know exactly what you mean by ‘higher level’, but, for me, it wouldn’t be about having the best-known names, or the most academic thesis to the curation; it would be about drawing in crowds, making art accessible, making it something people can engage with, want to go and see, talk about, revisit, and make part of their lives.

I don’t know how much you discovered Iași and the artistic area, but when we visit a place, we can either ‘feel it’ or not. Anna, how would you describe Iași, the Romanian atmosphere, and the kind of received you felt in Iași?

I had been to Iași once before, 16 years ago, as part of an exchange programme (BREDEX) to teach English over the summer. It was pure coincidence that I should end up returning for this, but a sheer joy, as I was able to meet up with one of my students from back then, with whom I’d kept in touch through letters and cards, and who had then been a child of just 12, but is now a qualified doctor. It was so wonderful to meet up again, and I felt so proud of her achievements. The welcome, as I remember from back then, was so warm, from everyone I met. I was showered with gifts and completely taken care of, taken out, shown around, hosted… Back then, in 2004, Romania was not yet in the EU; now, we are amidst Brexit and the UK is in the process of leaving it, so it was a strange feeling to return at this point in history. So much has changed in Iași. I truly didn’t recognise the city with all its new malls and shops and beautifully restored churches. But I’d certainly have known where I was from the welcome and hospitality I received.

Tell me more about the exhibition that took place at the Palace of Culture, how could we ensure that we create valuable artistic connections between Romanian and British artists in the future?

For starters, since this exhibition had to be shut down for most of its run due to coronavirus, we are hoping that, if it cannot be extended in Iași (which, of course, we’d love), that we might be able to take it to other venues – in both Romania and the UK. We also hope to get all the works online and to produce a catalogue – again, pending funding. If the exhibition does travel elsewhere, we’d certainly hope to encourage more of the Romanian artists to participate, were there to be another symposium, and we’d try to facilitate better introductions at the private view, or, perhaps, a dinner/lunch/some other event. That was perhaps the biggest omission in Iași, and, as one of the curators I take my share of the blame – the artists from one country did not have much opportunity to meet those from the other, and this, of course, is something to be encouraged, to feed ideas and artistic exchange. Whatever happens next, once there is a website to showcase the artworks, hopefully there will also be links to the artists’ websites, and then artists themselves might take the initiative to reach out to others whose work they find interesting. But, beyond this exhibition, I think it is important to organise further such exchanges – particularly now for the UK outside the EU – to take artists and their work to different countries, to experience different cultures, and to have them see and experience first-hand how things are for artists there. I would certainly be keen to work on future cross-cultural projects, with Romania and other countries.

Can you tell me more about the artistic scene in London? What does it mean to be an artist and what are the skills you need to be successful?

The artistic scene in London is dense. There are way more artists than the market can support. Galleries too are struggling with rent increases, being pushed to move from the centre of town. Artists themselves, of course, have always been at the forefront of these moves to former no-go areas, turning them round, and then being priced out as gentrification sets in. Many artists have had to leave London altogether as they simply cannot afford to live there, or to rent a studio. The gallery model is shifting so that many no longer even have a physical presence, but exist online, perhaps with a showroom open by appointment only, and, of course, attending international art fairs. It is all rather bleak, if you ask me! Artists need to be entrepreneurs to survive. So many schemes and courses are on offer, proposing to mentor them in business skills, marketing skills, and teach them how to write funding proposals, offering community engagement almost as the primary aspect, artistic skill as a secondary. Most artists who are successful either have financial backing from family or a partner, or else work hard in a second job – often teaching – to support themselves. Those that are lucky enough to be taken on by a gallery might end up feeling not that lucky after all, as they are pushed to produce more of what successfully sells, and to stop experimenting and developing as they would have, left to their own devices. I don’t mean to sound all doom and gloom, but I think times are hard for artists. And they will be being made a lot harder by the current global pandemic, since so many artists are losing all of their income as a result, and who, after this and the inevitable economic crash, will still be affording the luxury of buying art? That said, it is in times of crisis that artists come together, build communities, support one another, get creative, and new waves of ingenuity and success burst through. The #ArtistSupportPledge is a simple but effective example of this – artists selling their works via social media for not more than £200 each, with the promise that each time they have sold to the value of £1,000, they will buy a work by another artist. It was started on Instagram by the British artist Matthew Burrows, but soon went viral, and now artists all around the world are taking part, adapting it, and a lot of money has been fed back into the community (even where it comes from the community to start with, it is in circulation, and motivating artists to keep working and creating). So there is hope!

How important a role do you think an artist statement and explanation of the work’s concepts has to play? Traditional painting used to be a lot more figurative and rely less on conceptual meaning. What is your opinion on this?

I think I already answered this to a large degree. I am not a fan of conceptual art! At least, not when the concept becomes foremost, and the art itself secondary. A concept that needs explaining in a long statement or wordy press release is not art, it is, at best, something poetic; at worst, a failure. It is not always the artists’ fault – often they are responding to pressure since, as you say, this is so much the trend these days. Art students spend more time reading Deleuze than they do learning techniques of foreshortening or making their own paint from self-sourced pigments. Figurative painting – or painting of any sort – was, for a long time, highly unfashionable. It never ‘died’, as some critics claim, or had a rebirth or was rediscovered – it was always there. A true painter is a painter through and through and will always remain a painter, no matter what. And that is why groups like Contemporary British Painting were founded.

So, while I do think it is important for an artist to have a clear statement, I think it is more important for them to have good work that speaks for itself. And, if they do want an in-depth statement, I don’t think they should necessarily write it themselves – that’s why they’re artists, because they make art. If they could express what they envisioned in words, they’d be writers. Likewise, I write, because I’m a wordsmith; if I could put my thoughts into pictures, maybe I’d be an artist. That’s where I think artists and critics – or writers – need to work together. Just as artistic exchange between artists is key, so is artistic exchange between artists and critics, who can challenge with questions and feed with new ideas and suggestions and interpretations – which may or may not be what the artist intended of the work at hand, but, if the viewer sees it, it’s there, right? So, my advice to artists is to get a writer – any writer, not necessarily an art critic – to do your statement for you. Then it also carries more gravitas, as it includes ‘external value judgement’, which, to buyers and galleries seems to matter.

Anna, what are the challenges you experience when writing about an artist or an exhibition? What are your requirements?

Goodness, where to start?! Clearly, to write about an exhibition, I need to have seen it. Not for a preview, but for any kind of critical review. Images alone – even installation shots – won’t suffice, because you simply won’t get the feel for the flow of the show; the interactions and conversations between works. Likewise, to write about the work of an artist, I usually demand to see it in the flesh. Even the best quality .tiff files don’t give me a full sense of dimensions, let alone texture. And it is only by being present with a work that you get to contemplate it fully, build a relationship with it, interrogate it, and, in turn, interrogate your own response to it. Obviously, there have been occasions where I’ve had to write about works I’ve not seen in the flesh – and it’s becoming increasingly common for this to be asked of me – but I really am happiest when I can have that encounter, live that experience. As I’ve said: for me, art is about a visceral response, and this is not something that I will have in front of a laptop (or very rarely).

I love writing about artists – dead and alive! If alive, obviously I like to interview them where possible, again, preferably in person, or by skype or phone. Email is ok, but there isn’t that interaction. The artist prepares his or her answers in isolation from my thoughts, reactions and interruptions. I’m a researcher at heart, so I love to be given a challenge, whereby I can dig about in archives, or at the library, or online, and read around an artist or subject. I love to learn and think and connect ideas.

Reviews can be tricky, particularly if you know any of the artists involved – or if it’s a solo show of a friend. Often, I can love a person, but really not like their work all that much. In such cases, I might try to manoeuvre towards an interview instead, thus allowing them to critique and speak about their own work. That said, I often prefer reviewing work I’m not so keen on, as I always try to see it objectively, and look for what others might enjoy in it, or uncover what it was the artist was intending to convey. So, despite my objections to overly conceptual art, this can often be some of the most interesting to write about. If I truly, madly, deeply love a painting, because it has affected me intensely, I myself often can’t express this feeling and experience in words. Then I might try to explore what it is about myself that has meant I have reacted in this way. On such rare occasions, I allow my voice to come through and dominate, and the review becomes something more personal. Clearly I couldn’t do this all the time. I’ve had discussions with fellow critics as to how ‘critical’ we ought to be. My view is that we should try to remain objective. It is about the artwork, not the critic. Hence why I tend also to go more frequently by the label ‘writer’ rather than ‘critic’.

Also published in Romanian in the Ziarul Metropolis here