02/03/18

In Conversation with Alan Rankle

Art Bermondsey Project Space, London, 2016

AMc: Alan, you were trained at Goldsmiths and

there was conceptual art going on but, despite that, you remained pretty much

faithful to painting.

AR: I

didn’t expect it would take so long to do what I wanted to do in painting. At Goldsmiths

there was an emphasis on conceptual art, which was a radical, new position.

There were also some tutors who were among the best abstract painters, Basil

Beattie and Albert Irvin, and that was mainly what the college was all about at

that time. Going to the National Gallery as a young student and seeing, for the

first time, the art of the 17th and 18th century was the

outstanding influence.

My initial idea was to make artworks using

the subject of 17th-century art as a found object in the spirit of Arte Povera and so I was using

photography, making installations with projected images, taking for example a

slide of a painting by Ruisdael and making it go in and out of focus, on the wall,

and things like that. I decided I’d like to learn much more about how these

artists worked and to be able to quote them. In fact, there wasn’t a particular

moment, but something had stuck in my mind as being relevant. At the Greenwich

Theatre on a Sunday afternoon listening to some jazz, there was an avant-garde pianist

with a trio and, in the middle of all the improvising, he started quoting Bach,

which I recognised, and it occurred to me I would like to be able to do that,

you know, to quote these painters from earlier periods and use them in my work

– doing it for real. That’s how I got started.

AMc: You said quoting from the 17th

century – there are lot of art historical references in your work…

AR: Well, it’s changed over the years, but

that was the starting point, and in particular the Dutch landscape painters of

the 17th century – there’s something remarkable about them that got

my attention really early on.

AMc: But there’s a very contemporary edge to your

work as well – there’s sometimes a political comment, or is it a social

comment?

AR: I think it’s impossible to make paintings

about the environment without it being political. There have been lots of

influential people, John Berger for instance, whose critiques of 18th-century

paintings like Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs

Andrews made a fundamental impression.

AMc: You mentioned before that you see the arts

as being a kind of lightning conductor for the zeitgeist and that art-making isn’t something that you can plan. So

is it something that you don’t plan in advance at all? Do you know what your

painting is going to look like or do you have ideas as to what you’re going to

do?

AR: I have ideas that are really quite unfocused,

as if you were writing a film script and you didn’t have any dialogue or

locations, but you had a sense of the feeling you want people to have when they

watch the film. That’s how it starts. There’s something that I can’t easily put

into words – but, in a way, I put it into colours and so I walk around for a

few days – maybe a few weeks – and have an idea about an impression that

appeared to me as a dark red with a flash in it and I wouldn’t really know what

it was about. Then, when I start working, all the figurative elements come into

focus. I’ll get ideas and there’ll be a particular place that I’ve seen and want

to make a painting about. Yet it comes first as a kind of, it’s not really even

a feeling, it’s just like something that hovers in the back of your mind, you

know?

AMc: Do you make sketches at all or do you start

directly on to the canvas?

AR: Well, I used to make a lot of sketches. This

goes back to the Goldsmiths question, we weren’t really taught techniques as

such – there were some life drawing classes going on but there wasn’t anything

that really explained how paintings had been made over the centuries and so I had

to try to figure it out. I had a couple of friends who were interested in

traditional painting and we had to teach ourselves. There was quite a long

period where I was drawing a lot but not exhibiting, just trying to figure

things out.

AMc: Didn’t you spend some time doing painting

restoring as well?

AR: Yes, that was part of the plan always. I

realised that art restorers had an informed tradition and I started hanging out

with them initially and then getting some work and learning how to do these

things. Yes, they were a big influence, I could meet people working for Agnew’s

and Sotheby’s and they were grinding pigments and they knew exactly how

Rembrandt did something and why it was different to how Rubens did it, it just

seemed like a whole other world, and one I needed to understand.

AMc: Do you think you learnt more from that than

from college?

AR: Well, in that sense, yes – on the subject

of painting as an art.

AMc: Can you tell us a bit about the process of

making pictures? I saw an early film that was made of your work by Judith

Burrows and you were explaining how you worked and it was really physical – you

were using your hands to paint and so on.

AR: Yes, there was a lot of using hands and

fingers and forearms going on.

AMc: Do you still work like that?

AR: Yes, and I’m always evolving techniques in

different ways. You have to try to expand the vocabulary; to create a language

to make the paintings. There’s something that Francis Bacon said, that he was always

looking for new ways to put the paint on, and I think that’s quite crucial – it

keeps it fresh and it keeps the vitality going as well. It’s important to me

that the painting doesn’t just stop on one plane or style. What I’m trying to

do is keep on undermining the concept of having a style and letting other

unexpected elements in.

AMc: Recently you’ve added photographs to your work,

too..

AR: Yes. I had some commissions, from an

hotelier, to go to foreign cities and make paintings that reflected the city

and also the art of the city. I had the idea of making photo-montages as

studies from shots of the locations. The first one Serpentine was for a hotel on Hyde Park, a Rankle & Reynolds

project actually, and the second one was in Paris where I asked Rebecca

Youssefi, my assistant on some projects, to do the photography. So there became

a random element where I’m not even aware of what she’s looked at or shot until

I see the images – she makes photo-composites, like the sort of thing

Surrealist photographers were doing.

If you make an image where you have two or

three different layers, you get these unexpected narratives that no one has

ever seen before and yet there’s an uncanny feeling that you’re looking at a

subliminal reference to the subject. In the case of the Paris and Venice works,

you’re getting some very interesting signals about what the city is about. We

print the montages on to already painted, textured canvases and then carry on with

the painting with the layers of printed imagery embedded into the paint. It’s a

modern equivalent of what Warhol and Rauschenberg were doing with silkscreen. I

then use this as a basis for overpainting, leaving fragments of the photomontage

coming through like pentimenti. It’s

a new thing, I’ve never done it before.

AMc: You’ve done other collaborations though, you

said.

AR: Yes, quite a lot, and I’m very interested

in doing that.

AMc: And do you see that as part of your own

practice, or is it separate?

AR: It’s definitely part of what I do and, in

a sense, whoever I have collaborated with, when you look back at it, I’m the common

element. I like the way other people’s ideas come at you in a quite random way

– it’s completely unexpected and you have to respond to it. I slightly envy

musicians who are in articulate ensembles where they’re all improvising together.

I’ve always been attracted to that and, yes, through collaborating with other

artists on a particular project, you can get close to it.

AMc: Do you listen to music when you are working?

AR: A little bit.

AMc: What kind of music?

AR: It changes. If I do listen to music, I

tend to listen to something that I choose in the morning and then play it all

day – obsessively. So, if it’s an album, it could be – one of my favourites – Sibelius

or maybe Bob Dylan. I’ll choose one and it gives you a mood; a particular piece

of music fills the room and gives you a kind of energy and when it stops I just

press the button and play it all over again – which is perhaps not so nice for

anyone else in the studio! It’s like creating a tone around you, a sonic

environment.

AMc: I guess it leads to the question that we

sort of touched on, but how much of your painting would you say is an

instinctive emotional response and how much of it is guided by rational

processes?

AR: I’m not altogether sure how much a

rational process comes into it; I can see what you mean and clearly I have to

be quite controlled to do certain things. If we consider these paintings we are

looking at today, they are all from a similar series so they have things in

common, they have a certain look and they were painted to reflect the style of earlier

paintings and other periods of art are referenced and I need control to do

that. Yet working in this way does come out of being instinctive, and then it

goes back to being instinctive quite quickly. There are artists who’ve worked

in equally eclectic ways. If you think about the assemblage pieces of Rauschenberg,

for instance, he would take a photograph from here or there and put on these

silkscreen images and then, instinctively, paint across them. It’s not that

different really, he was doing a similar thing there in just jolting you from

looking at something in a particular straightforward way and, I think, if I add

anything to that way of working, it’s to make it more integrated.

AMc: When you are not using the photographs, you

are painting first, do you paint from photographs? Do you paint outdoors ever

or is it all done in the studio?

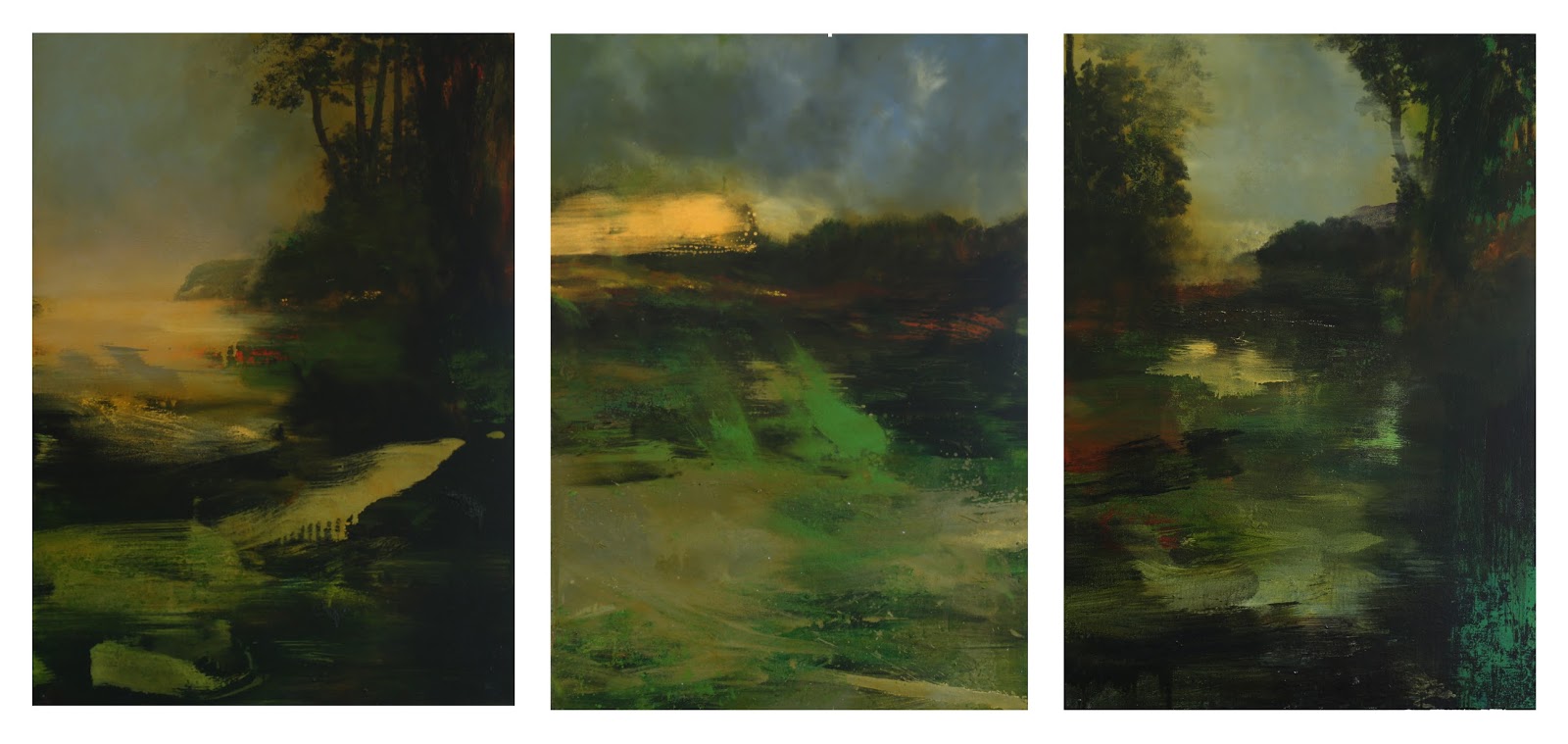

AR: I did a lot of painting outdoors and a lot

of the locations in these paintings are from particular places that I keep

going back to. So this series is called River

America – it’s not a title for one

painting, it’s a concept. It’s about a place in New York called Sands Point on

Long Island. I was just attracted to it, I started drawing there, and I went

back a few months later and took photographs and made more drawings. I’ve tended

to build up a sketchbook about different places but now, at this stage, I’m

painting places from memory. It’s like if someone writes a song and they start

playing it in a different way, they’re really playing variations on the memory

of the song and I can relate to that.

AMc: You’ve mentioned that you work in series. Do

you work on one series at a time? What defines a series for you?

AR: Well, it becomes a series later on, you

realise that this painting is linked to these others and it hops back and

forward through the years. I’ve just started again with the gold paintings, which

are here in this exhibition. I began the series Further Tales from the Beach House in 1992 when I rented a modernist

beach house, with a 360 degree view on the top floor, about 50 metres from the

English Channel, and I wanted to make some paintings that would reference the

way the elements were crashing into the cliffs and disgorging landslides, and

it occurred to me I could do so using metal leaf. Working with sign writers’

gold leaf, which contains copper, I could paint on it using chemicals that

would alter the metal leaf’s surface and release the copper essence as

verdigris. The process became a metaphor for the way the wind and the rain and

the sea were changing the cliffs. So that was in 1992 but I have just started

doing some of those things again, so they are all part of a series but it’s not

a logical thing really and I do lots of different things all at the same time.

AMc: Talking about gold leaf – you’ve said before

that you make a painting and it becomes an object of passion…

AR: Did I say that?

AMc: You did! [laughs] I was going to ask you to

explain what you meant by that but if you don’t…

AR: I think I know what I meant. Going back to

some of the artists who were early influences, I was very keen on Joseph Beuys,

Jannis Kounnelis, Yoko Ono and then Gilbert and George came along. They did a

very interesting thing to create art from their total physical presence. The idea

that artists are catalysts, not only for people’s ideas, but also to show the

art within people’s lives, where the art is not just about looking at the

drawing on the wall but actually is

the wider context. From Beuys saying ‘Everyone is an artist’ and doing very

similar things with his performance lectures and then, significantly, leaving

iconic traces of his performances – blackboard, felt, fat and so on – as relics of the experience. For me this is

where painting comes in. I was thinking about those kind of Tantric objects,

you know, from India and Tibet – objects that people used to meditate on, or

via – they have a certain tangible quality, a kind of magical quality. They’re

objects yet also a form of transport towards other ways that you can see

things.

I like the idea that you can make an

object, a painting, that’s totemic and that has some energetic power in it. If

you can make an artwork that does this, it transforms perception, it’s a

catalyst for the way you can just notice things in a different way. In the 1970s,

when I was getting ideas like this in my 20s, there was a quite a drug

influence on my generation at art school. I have to own up and say these were

the days of LSD and reading about ethnic Shamen, the Hopi Indians and Sufi

philosophers. So this might have been an influence on how I interpreted Beuys

or the Arte Povera artists. All the same, it’s about art as magic, yet rooted

in square, straightforward things you can see.

AMc: At least that’s what you are trying to

achieve really to go from there.

AR: I’d like to, yes. There was an experience

I had in the British Museum, there was a sculpture in one of the galleries – I

think it’s in the Oriental Gallery Number 2 – of a Bodhisattva; it represents

someone who’s going to become a Buddha. It was just the way the sculpted figure

was sitting, it was a kind of yogic posture and it just got to me. I looked at

it and instinctively began to move – there wasn’t anyone around in the gallery

– and I just got into the posture the statue was showing me and the immediate

effect was quite electrifying. I realised that by simply assuming that pose, energy

can suddenly ripple through your body, and I thought this is real art, you know,

who was this artist? Can you get your art to do this? So it’s always the goal

that the art transforms things when people look at it.

AMc: You were talking yoga postures, but you’ve

also studied T’ai Chi quite a lot.

AR: Yes, I was becoming familiar with T’ai Chi

at the same time. It came about incidentally, I was trying to find someone who

could teach me about Chinese Ch’an and Zen painting and so I just started to

fall in with people who were studying Chinese art.

AMc: And did you like studying with them, the

teaching process and what they were doing?

AR: Yes, enormously. I’d written my thesis at

college on the history of Chinese landscape painting and the reason I wanted to

find a teacher is that, after three years of being quite academic, I realised

that I was ready to really learn something. So yes, that’s how it came about.

AMc: Actually in China?

AR: No, I tried to get to China, but you

couldn’t easily in those days. I went for an interview at the embassy in London

and I was being hopeful, you know, and I was shown into a very big room and

there were two chairs, both facing the front by a little table with flowers on

it. This guy came in and sat down and looked straight ahead and I was invited

to sit and we didn’t really glance at each other. ‘Why do you want to go to

China?’ I’m staring at the wall and I said: ‘I’ve been studying Chinese

landscape painting and I want to tour around these ancient sites’. The minute I

said that I could tell he realised that I didn’t know what I was doing at all.

So the interview was over very fast! They weren’t letting anyone in, apart from

diplomats. So I’m grateful to my teacher of Chinese art in London, Liu Hsiu

Chi, who was massively important to me.

At the same time, I was studying

with the art restorers, so it was all study in those days. I was watching some of

my friends becoming quite established artists while I was still at the drawing

board stage, but it’s what I wanted to do.

AMc: What about the scale of your work? You are

known for doing quite large pieces, commissions in particular.

AR: Yes, they’ve just come about really. I

mean you just sort of say ‘yes’.

AMc: That’s because you are commissioned to do it

that size or because you are particularly keen to do large-scale works?

AR: For some of the commissions, I rent a

temporary space, but this one here is the largest I could have in my painting

room and even this size I have to take them through to my friend Oska Lappin’s

studio and open these double doors then hoist them down on a rope on to a flat

roof. It’s mad. But I would rather like to be able to make canvases the size of

this wall – I just need the right room to do it in.

AMc: What about the title of this show, Pastoral Collateral – where does that come

from?

AR: I wanted to relate ideas about historical,

idealised, pastoral landscape in art to the grim reality of the environmental

crisis that we are in, which isn’t just an environmental crisis anymore, it’s a

totally impregnated social and political crisis heading towards disaster. Considering

the historical origins of the genre in relation to my own paintings, I wanted

to convey the irony implicit in how the 19th century Romantic

movement, with its emphasis on the idyllic natural world of an imaginary past,

was sponsored by people who, having made gigantic fortunes out of the

Industrial Revolution by building their empires on the slave trade and the

criminal use of the Enclosures Acts to force the poor from their traditional

peasant homes to work in their factories and mills, also laid the foundations

of environmental pollution on a catastrophic scale.

Turner and other artists were commissioned

by the kings of the Industrial Revolution to do the Grand Tour to pick up ideas

from artists such as Claude Lorrain and Poussin, who were themselves employed

to evoke the fantasy of a golden age, a sort

of Narnia in Ancient Greece and Rome, where people talked to animals and fucked

gods.

While you can’t look at any period of

history without seeing similar scenarios, where the art is created for the

tyrants and oppressors, this dichotomy of the landscape of Romance is particularly

and acutely about the subject that I’ve been interested and involved in. It’s impossible

to work in landscape art without being politically active, and I thought let’s

put this right up front. So that’s the title. The superb catalogue essay by

Judy Parkinson explores these themes with some panache.

AMc: So it’s important to you for people to know

this sort of back story, if you like?

AR: Well, it’s been a motivation. I’ve played

around on the outskirts of this theme over several exhibitions. I’m trying to

stimulate people’s ideas and precipitate a dialogue.

I’d always wanted to relate to

landscape painting in the way Francis Bacon transformed portraiture by showing

the violent undercurrents in the human condition and using body language to

show how both wretched and exultant the inner self can be. Twisting it around

in the paint until eventually he’s created something awesome and of singular

beauty.

AMc: Do you think what you’re producing is

beautiful? Do you want it to be beautiful?

AR: I think it might be. I’m not sure. But I

like the idea that it’s a catalyst for other people’s ideas and I think that’s

beautiful. I can see there’s a quality that links the paintings and that’s my

idea, really, of what I like to look at.

AMc: You talk about people’s ideas, and I’ll open

for questions in a minute, but can I ask just one more thing? You mentioned about

figurative elements and I just wondered actually – I can’t see any in here, but,

for example, take the stag painting next door – is there a particular

significance in the piece?

AR: Yes, there’s a significance. I got the

idea from a particular painting in my favourite museum, which is the Musée de

la Chasse au Nature in Paris. It’s a museum that used to be dedicated to hunting

but now also includes exhibits about the environment. There’s a fantastic

collection including this grand painting by an anonymous artist of the 19th

century. It’s a painting of a stag crashing into a banqueting hall and flooring

the table as it collapses. The antlers are there and the tablecloth, with all

the dishes flying everywhere, and the look of terror on this creature’s face. I’ve

just lifted it really, I took the image and started drawing it and then copied

it in, so far, about six paintings. But I moved the animal from this pantomime

situation into the actual landscape. The beast is panicking because it’s

running scared and then it’s fallen and doesn’t know what the hell is going on.

When I was making the early stag

paintings, Sarah Lloyd was writing a piece for a book to accompany the exhibition

and she asked me to explain them. I said: ‘Well, the animal is running and the

title is Running from the House, and

it’s a metaphor for nature itself being overrun and being hunted’. So that’s

where the stag came from and these themes appear and reappear.

AMc: Does anyone have any questions? Do say ‘yes’!

Q. In terms of your process, you mentioned

your interest in themes of Chinese art. Is being conscious in the present important

for you in your painting?

AR: Being conscious in the present is the

whole point.

Q. Is it why you paint? Is it your compulsion

to paint?

AR: I think artists feel more when they’re

painting – you feel more alive, and you feel more with it. Francesco Clemente

once said that if he went more than a couple of days without painting, he’d

feel sick, and the minute he’d pick up a pencil and start drawing, he felt more

alive and healthy. I think you can increase your perception by drawing. Michael

Craig-Martin, one of my tutors, thought of drawing as a way of thinking and so,

if you are drawing, something unique happens in the way you perceive – we are

talking about observational drawing now, where you are looking at a view or a

figure or a tree or whatever, and what happens to your mind when you draw. He

thought it was a way of thinking and it makes you more alert. I think it shows

you how you can shift your attention from one way of looking at things to

another, and I’ve found that really important.

Q. And that’s something else I wanted to

ask you actually, about the meditative process and the fact that you were so

inspired by sitting in front of a Buddha and doing yoga – do you still practice

yoga?

AR: It wasn’t really quite like that. T’ai Chi

is a martial art, you know, and yes, I practise, sure, yes.

AMc: But we won’t find you in the Oriental Gallery

Number 2, striking a pose?

AR: No.

MB: It’s great having you here, Alan, having a

conversation with Anna, it’s really wonderful – a lovely treat from the

gallery’s point of view. I would like to ask you about your next projects. What

are you doing in the next six months?

AR: I’ve

been invited to work with an Italian interior designer, Veronica Givone, and we

are going to transform six suites – so called VIP suites – at the Lowry Hotel

in Manchester. So, if you are a famous footballer or a member of a rock band

and you go to Manchester, you’ll get to stay in the rooms that we designed.

BH: Do you think that the average person who

buys your paintings and comes across your paintings actually gets the message

that you are trying to put across and how important is it actually that they

do?

AR: Well, they get the message that they get.

I mean, that’s it, isn’t it, really? I can’t force it. I’m not going to test

them. Some people might get it completely wrong, of course, but if it’s a

catalyst for a different way of looking at things, then that’s fine by me.

That’s the whole point. I had this idea that there’s art that can be a gateway

to a greater freedom in contrast to art as propaganda, which closes down

options. It occurred to me, if you draw people’s attention to a point,

the way tabloid TV does, or the kind of false political advertising, manipulating

public opinion like a corrupt politician, like Goebbels for instance, it’s also

drawing people’s consciousness into a point – more and more blinkered; and

really great art opens wider possibilities and that’s what I’m trying to do. I

think great art is a catalyst for being more aware instead of being led by the

nose. If that works then it works. I can’t control what people are going to

think, but I hope they will start thinking – that’s the thing.

AMc: Any other questions?

JB: I have one. I have known Alan for a long

time and I love his colours and he draws you into the picture. Looking at all

of the works here, they’ve all got side positioning things and you are drawn

through into the distance, which kind of explodes at you, and yet you are always

drawn through. There are very beautifully crafted trees in the style of a 17th-century

pastoral landscape. You are drawn through to this sky with beautiful colours. I

think you had that throughout and yet now, you are still using that, but they

are changing and this exhibition is slightly different from the earlier ones

but they have that same wonderful technique..

AR: I guess I’ve been doing things that look a

bit alike for quite a time, it’s taken me a lot longer to do what I wanted to

do and I thought maybe I should be a bit faster in moving on to some other

subject.

JB: That’s their beauty, they are alike but

different and they’re not – they are all different and yet –

AR: I like to think it’s an ongoing series, I

call it Landscape Painting Project

and the idea is that I can tie it up and put it in a box one day and move on

and do different things. But, at the moment, it’s still relevant; I’m getting a

lot of ideas and wanting to follow this route. I’m glad you’ve liked the

paintings over the years.

JB: What would you want to move on to do?

AR: I’m going to make some whole room

installations that use everything from painting directly on the walls, to

objects I’ve made, plus projected imagery and sound. It goes back to my roots.

I’ve accumulated a lot of objects, some that I’ve made, and found objects that

I’ve done something with, and they’ve all gone down to the studio in France to

be assembled.

I’m interested in the works of Larry Bell,

the conceptual artist from Los Angeles, who, in the 1970s, made plates of glass

that drift into mirrors, which I can relate to as landscape interventions,

referring to the 18th-century concept of the Claude Glass.

Sculpture that can alter the environment

with subtle reflections and refractions of light – that interests me a great

deal.

Q: What’s your starting point when making a

painting? Do you start with a drawing or do you actually start with the paint

and making shapes?

AR: I’ve always thought that if you put a drawing

on first and it’s wrong then it shows through, but lately these paintings are

all about things that are wrong and show through. I like the idea of pentimenti, when you see something

that’s already there but slightly covered up, and, by using layers of glazes, I

can do that. These paintings are all started with a red imprimatura like they would have used in the Venetian School, where

they would make a canvas and colour it in a dark red and draw the shapes of the

composition in monochrome shades of dark and light, the idea being that –

particularly if you were painting blue, a sky or the robe of the Virgin Mary or

something – the blue really stands out because, if it’s on white, it tends to

be chalky. So I often start with a red or an ochre background and just start

painting.

Q: Yes, but would you prefer to draw, say,

landscape drawings, where you have a basic idea of composition?

AR: I

tend to draw when I’m travelling. I have a lot of pocket sketchbooks and I draw

the shapes of canvases and sketch what I’d like to do, then I almost

obsessively do repeats of the same image until it becomes just right. It’s

quite a commitment to do a large painting like this, and sometimes you have to do

a lot of work before you know it’s going to work. So I draw compositions,

scribbles really.

AMc: I have

a question relating to this series, these ones here, about the text and when

you started adding written lines.

AR: The text here was suggested to me by a

friend, Tom Burke, who has written about my paintings and is also an

environmentalist; he’s done some amazing things like helping to found

Greenpeace and running The Green Alliance. He was first of all saying we should

read a lot more TS Elliot and get ideas from The Wasteland, and then he quoted a fragment of a poem by Rainer

Maria Rilke, ‘Strange to see all that was

once relation now fluttering hither and thither in the breeze’. And the

minute he said that, it really struck a chord. The author was writing about a

premonition of the First World War and how everything you think is real, that

you can rely on and the way you think you know things, can suddenly evaporate completely

into chaos. I think that’s a good metaphor for modern times. Politically,

environmentally, we are standing on quicksand in every area of life that you

can think of. So I’ve been writing the quote on the canvases.

Q: Of one poem?

AR: Yes, for a couple of years. Yet the

writing, the calligraphy, becomes hidden, There is something magical about the

power of writing, isn’t there? I have a quote in mind and, at some point while

painting, I feel like writing it on the canvas, and even though it becomes

abstracted and it’s sublimated and you can’t properly read it, in a strange way,

it still retains the energy of the handwritten word. If you look at the really

abstracted types of Oriental calligraphy, you can sense this. Within the

different styles of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy, there’s very formal script,

and then there’s a more elegant style where the words are there, the characters

are there, but it’s also kind of pictographic where the calligrapher tries to

give a hint as to the subject in the way that the characters are made, like a

concrete poem. Then a third style, the free or grass script, is almost

completely abstract, yet for someone who is a real connoisseur, it embodies the

essence of the poem or the text within it. If someone can do that, they’re

elevated to be a master calligrapher.

MO’R: Alan, the painting of the deer, is there a

direct link with Monarch of the Glen?

AR: I recall Monarch of the Glen as the kind of art that I’m not so interested

in. The apotheosis would be Peter Blake painting a pop version for Paul

McCartney – how unreal is that? I did have an experience, though, when I first

began the Running from the House

paintings. I was in Copenhagen and my friend Bjarne Neilsen came into the studio,

took one look, and exploded into laughter – he said ‘You can’t do that here,

not in Denmark, it’s only two years ago that everyone threw their antique stag

paintings in the skip!’ I’d thought of my take on deer paintings as a comment

on how society relates to nature, yet on reflection I should own up. I also had

a commission to make an unapologetic, monumental stag painting for Marco Pierre

White to hang in a restaurant. So I guess I did my own pop version, just like

Peter Blake.

MO’R: What’s this stag doing for you, the other one

next door?

AR: Well, it’s about everything I’ve said: the

chaos and the sense of anxiety in nature… and then, I suppose, it’s about sex… [Laughter] …if I’m really answering the

question. It’s a fairly esoteric thing, yet you know that energy flows out of and

around your body when you’re highly aroused, and don’t you think there’s often a

kind of antler effect that comes out of people at those moments – like a subtle

lightning you can see flashing around the person – and it’s like antlers?

MO’R: Well, the stag was kind of Shamanic in Celtic

culture.

AR: Yes, and also in stories about Herne the

hunter and the stag. I think there’s a lot in those myths, these stories go

back to very early times. I think they have meanings that are more fundamental

than commonly thought. I’m making some works based on the Titian paintings Diana and Actaeon, and The Death of Actaeon where the Greek myth seems overly simplistic to me and

just not right.

The idea that there’s a young shepherd, who

inadvertently comes upon Diana and her nymphs bathing and so she immediately turns

him into a stag and hunts him, kills him and the dogs eat him.. it’s like a cartoon.. I think the myth was

originally about deeper things than punishing an accidental voyeur, suggesting

symbolic ideas about men and women that come from a much earlier time. I had

the mad idea that by painting and drawing this I could somehow get an insight into the meaning of the

myth. So, it’s an ongoing project.

MO’R: Well, good luck with that!

AR: Thanks! I’ll try my best.

[Laughter]

AMc: You couldn’t say more to follow up on that. Thank

you, Alan.

Audience

questioners: Q Unknown SM Serenella Martufi, JB Judith Burrows, MO’R Mark

O’Rourke, MB Michael Barnett, BH Ben Hamilton

Images: all © the artist

Study for River America

2013

oil on canvas

triptych, each panel 84x60cm

Untitled Painting (de Loutherbourg)

2015

oil on canvas

80x100cm

Untitled Painting XI (Herne)

2015

oil on canvas

160x190cm

Also published in the International Times