18/07/18

‘The end is where we start from’: Laura

Moreton-Griffith’s history painting of the future

In a series

of lectures delivered at the University of New Brunswick in 1950, professor of

political economy Harold Innis decried the ever-increasing loss

of respect for the past and the future. This ‘present-mindedness’, as he termed

it, was, to his mind, a symptom of capitalism, which had fostered the

measurement of time, facilitating the use of credit and the rise of

exchange-based calculations of futures that were deemed predictable and

insurable. In his 2016 essay, ‘A New Politics of Time’[1], Professor

John Keane similarly discusses the ‘myopia of democracy’, ‘encouraging a fixation

on the here and now […], discriminat[ing] against younger generations [b]y

allocating health care resources for the elderly and financing social insurance

schemes out of current taxes […],turning a blind eye to long-term environmental

degradation and […] the risks associated with bio-genetic engineering and

burgeoning population growth’. These beliefs, Keane adds, are all ‘egged on’ by

claims that we are facing ‘the end of history’ (as proposed by the American

political scientist and economist Francis Fukuyama in his 1989 essay of the

same name [2]) and

the arrogant conceit that we have solved all the problems of the past.

The idea of

a politics of time plays a key role in Laura Moreton-Griffiths’ dystopian

installation, Truth Lies Within

(2017). A ‘three-dimensional history painting’, it entraps and entwines the

viewer in the act of storytelling, implicating her in the denouement of its

disturbing plot. Walking amidst the ensemble of characters, she takes on a

participatory role, bearing the burden and the guilt of every false decision. It

might be described as a postmodern, post-truth, post-whatever-you-like scenario,

but this would, in fact, be a misnomer, since the real key to Moreton-Griffiths’

work is the fact that it stands outside of time, or, at least, outside of the

linear model of time on which modern – western – history is predicated. Instead

Moreton-Griffiths employs the concept of non-linear, cyclic time, and weaves

the elements of her work together as an author might weave a work of

speculative fiction.

The term ‘history

painting’ was introduced in the 17th century to describe

paintings with subject matter drawn from classical history, mythology

and the Bible. Derived from the wider sense of the Latin word historia, it essentially means ‘story

painting’ and is a genre defined by its subject matter rather than any specific

artistic style. In the 18th century, the term began to be used to refer to more

recent historical subjects, usually depicting a moment in a narrative story,

rather than a static subject. Typically a history painting would be large

scale, made as a propaganda piece for those in power to represent and demonstrate

the effect(-iveness) of their regime. For Moreton-Griffiths, however, history

becomes the future – and a future which, discordant and undesirable as it

seems, ‘could’, as Margaret Atwood says of her own works of speculative

fiction, ‘really happen’. The social structures and power relations necessary

are all already in place; they are all already (mis/dys)-functioning – the

artist merely mirrors and exaggerates what she knows.

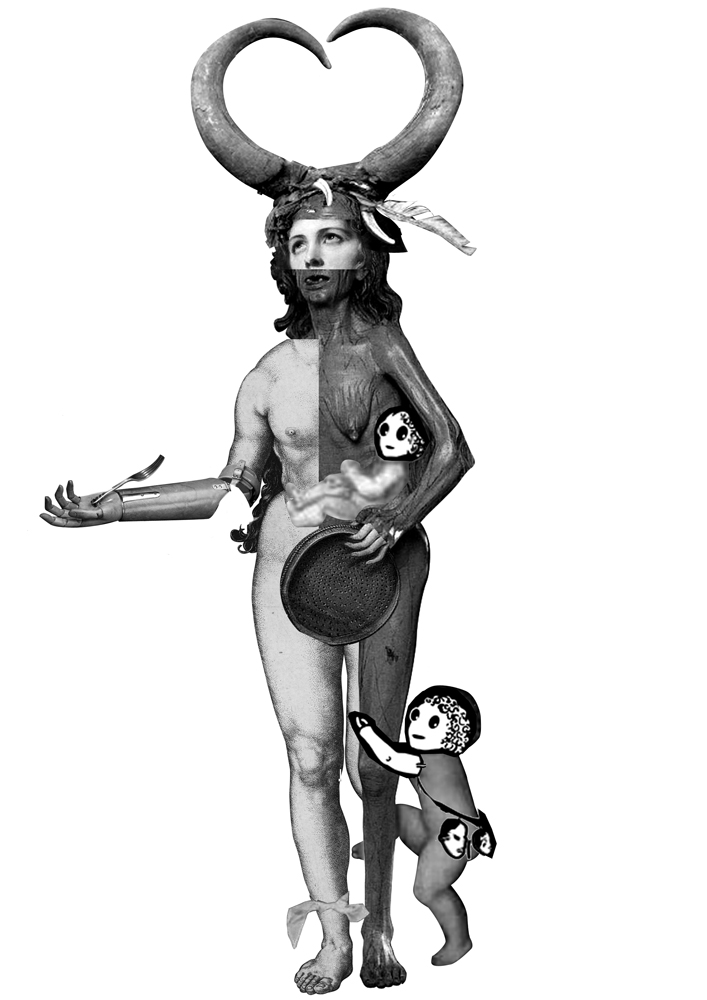

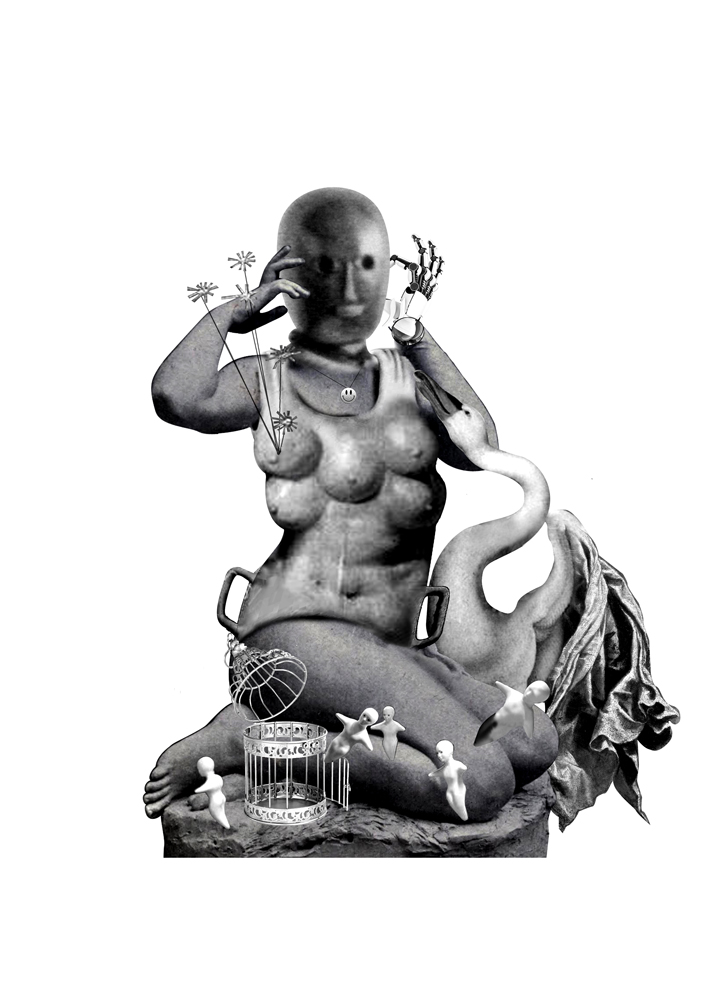

Each laser-cut

standing figure adds to the painstakingly constructed tableau of cultural and

art-historical references, conflating past, present and future in one pictorial

event; a timeline of interacting and cascading cause and effect. Classical and

Renaissance sculptures stand in ruins, symbols of the true democracy of times

gone by, when oral tradition enabled the collective achievement of a healthy

balance between time gone by and time still to come. Semi-bionic, the victims

of technology, these sculptures are transitioning to computer-directed

automata. Yet even these robots are at risk, positioned – helplessly rooted –

amid armed putti on hoverboards, swooping menacingly, dancing the dance of the

demon alongside dragonflies, which, on closer inspection reveal themselves to

be military drones (sourced, Moreton-Griffiths says, from the CIA flickr site).

Virtual reality headsets, voodoo dolls and segments of indecipherable binary

code: the closer you look, the more threatening the scenario reveals itself to

be. The work collages themes of propaganda, false information, and algorithms

that target us with personalised political messages. The installation, or

combination of elements as a whole, takes precedence over individual painted or

constructed elements: the crowd, rather than an individual; the complex and

daunting narrative of a mob. Them against us. But who is the us? Clearly, the

‘Other’, the lesser, the victim. Do we, the ‘Othered’ viewers, then stand

united, or is it each man and woman out for him- and herself?

Moreton-Griffiths

wants her timeline to be multidirectional – like a choose-your-own-ending teen

fiction book – but does this allow for undoing one’s false decisions,

redressing one’s mistakes, redeeming society from the sins of the past? In One Dimensional Woman [3],

philosophy lecturer Nina Power speaks of ‘a feminism of failure’ – a model in

which women would have the freedom to fail, to be uncertain, to question, experiment

and ultimately define – and redefine – themselves. Might Moreton-Griffiths’

dystopia be read as a dystopia of failure – a dystopia that might yet be

inverted, rescued, even rendered utopian?

Perhaps what

is represented is a form of limbo, or purgatory, an indefiniteness of time as

much as of identity and direction, a place of looping back in order to move

forward, or of looping forward in order to move back. A place of the conditional

perfect, of would-have-beens and could-have-beens, but not necessarily ought-to-have-beens, for in a model of

non-linearity, such uni-directional modals cease to exist. Anything becomes

possible. The actors becomes the directors. We, the protagonists, build and

arrange the next act. ‘Time present and time past/Are both perhaps present in

time future/And time future contained in time past,’ writes TS Eliot in Burnt Norton (1935). ‘What we call the

beginning is often the end/And to make an end is to make a beginning/The end is

where we start from.’

© Anna

McNay, July 2017

Laura Moreton-Griffiths’ website

[1] John Keane, ‘A New Politics of Time’ in The Conversation, 2 December 2016, http://theconversation.com/a-new-politics-of-time-69137 [accessed 16/07/17]

[2] Francis Fukuyama, ‘The End of History?’ in

The National Interest (16), 1989, pp3–18 https://www.jstor.org/stable/24027184?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents [accessed 16/07/17]

[3]Nina Power, One Dimensional Woman, Zero Books, 2009