06/05/17

Travelling

through Time and Space: Meaning and Interpretation in the Work of Nick Malone

Nick Malone would

rather think of his current practice as that of a painter who writes, than a

writer who paints. His career trajectory has taken him from writer, with a

sideline as a literary academic; to painter; to painter employing fragments of

text in his works; to, most recently, author (does one say author, or artist?)

of a graphic novel, purporting to tell the (abridged) story of his far from

mundane life. For his exhibition at Art Bermondsey Project Space, Malone will

bring together this graphic novel, as it currently stands, with a soundscape

bringing to life its final, dramatic sequence, and some of his recent, large

three-dimensional paintings, all of which draw from what he describes as his

‘personal and private mythology’. In such a scenario, without knowing the

artist’s story in advance, one might well wonder how the visitor is to pinpoint

any meaning in the work, or, more importantly, whether there even is such a

thing. What can one hope to find? ‘They do have meanings,’ says Malone, of the

assorted works that will be on display. ‘And they all emanate from this common

vision. But there is no absolute […] There are differences in emphasis.’

Using a model,

whereby the subject matter and artist’s intention are external to the work of

art as an aesthetic object, Virgil C Aldrich delineates a difference between an

artist’s intention and the meaning of the work.

‘Just as someone might say something he did not intend to say, so

may an artist fail to get his intended message across. […] Thus do the material

and the medium have their own powers of expression which may run counter to the

intention of the user, depending on how he deploys them.’[i]

He concedes, however,

that knowing both the subject matter and the artist’s intentions ‘tends to

assist one to grasp what is in the work’. Malone, however, would not see

such a difference in intention and received meaning as a failure. The

‘differences in emphasis’ he refers to are, if anything, quite deliberate,

stemming from his deep-seated intrigue with ‘ambiguity, and the possibilities

of multiple significance in meaning’[ii].

Malone’s paintings

deliberately eschew a hierarchic structure, as he seeks to introduce chance

into his practice, initially

by pouring paint over hidden objects, creating a 3D

landscape, and it is their mixed-medial nature, in which word and image

simultaneously elucidate and obfuscate one another, ‘sharing the same space,

though remaining clearly distinguished in terms of spatial relations, kind of

intelligibility and often the division of labour,’[iii] that

engenders what Simon Morley terms ‘topographic’ space, namely space subsuming

both time and space.[iv]

Accordingly, as well as subverting hierarchies, Malone’s works breach the

boundaries of painting, considered since GE Lessing’s seminal essay, Laocöon:

An Essay upon the Limits of Poetry and Painting (1766), to be a medium

concerned solely with space:

‘Painting, by virtue of its symbols or means of imitation, which it

can combine in space only, must renounce the element of time entirely,

progressive actions… cannot be considered to belong among its subjects.

Painting must be content with coexistent actions or with mere bodies which, by

their position, permit us to conjecture an action [ie. imply a narrative].’[v]

In Malone’s work,

both space and time play a role, and a certain level of ambiguity necessarily

arises depending in part on which plane you view it from. In the graphic novel,

the level of diachronicity, or ability to travel back and forth through time,

is made explicit by the use of windows

cut from one page through to the next (and back), an idea developed from Richard McGuire’s Here (Pantheon Books, 2014). This time

travel might also be seen as space travel, however, but specifically space

travel between inner and outer worlds. As Malone explains, drawing inspiration

from the lines of TS Eliot’s The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock, with

which he opens his graphic novel:

‘There’s always the “you” and the “I”, and the “you” is the

Makepeace [a character in the novel], who opens the trapdoor into another

world. […] The two worlds co-exist and you can go between one and the other.

There’s this constant dialogue between the inner and the outer worlds.

Imagination comes from this. It’s the human psyche.’

By employing word

and image side-by-side, or, rather, interwoven and meshed, one on top of the

other, Malone’s works insist upon two distinct modes of information gathering –

one involving the visual scanning of the image and the other the reading of the

words. The former mode allows freedom of interpretation and uninhibited mental

and sensual movement, while the latter confines the reader to a predetermined

route, constructed from a row of letters to be deciphered from left to right or

top to bottom.[vi]

According to bi-lateral models of the brain, image interpretation takes place

in the right brain, the site of non-logical, intuitive skills, while language

is sited in the left brain, which shows a bias towards the rational, logical

and discursive. Morley concludes, therefore, that the interpretation of word

and image not only occurs at quite different speeds, but, involving different

orderings of perception, ‘we simply cannot do both simultaneously’.[vii] Thus

returning to Aldrich’s discussion of the origin of meaning, the material and

the medium of Malone’s work clearly exploit their own ‘power of expression’,

with word and image each drawing the viewer down its own route. Bringing the

overall picture together in one’s mind is not so much a process of discerning

the meaning as of creating an interpretation, and it is this

interpretation that offers the full aesthetic experience.[viii]

While Malone’s

work may arguably have one central subject matter (recall: ‘they all emanate

from this common vision’), his use of multiple media and materials means that

there is no direct mapping of meaning to interpretation. This situation, of a

‘quantitative abundance of the forms […] correspond[ing to] a small number of

concepts’, is equally a result of the model employed by Roland Barthes, in his

analysis of myth as a metalanguage,[ix] and

this model might be carried over to explain, in greater depth, the presence of

ambiguity and multiplicity of interpretation in Malone’s work – work dealing,

as we have heard, with his ‘personal and private mythology’.

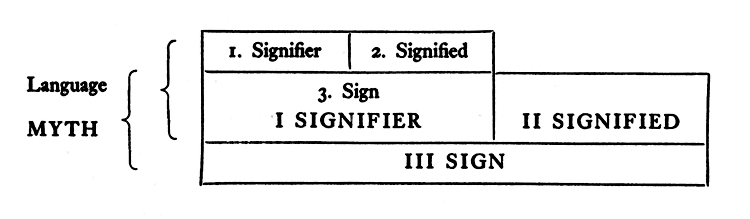

In Mythologies,

Barthes takes Ferdinand de Saussure’s model of the linguistic sign,[x] as

composed of the signified (the underlying mental concept or form) and the

signifier (the arbitrary material aspect of the sign, with which the signified

becomes associated) and proposes a secondary or meta-system, whereby the

mythical sign (the myth) is composed of a signified and then a signifier,

itself comprising a pre-existing sign, the meaning of which is already complete.

This mythical

signifier ‘postulates a kind of knowledge, a past, a memory, a comparative

order of facts, ideas, decisions. […] When it becomes form, the meaning leaves

its contingency behind; it empties itself, it becomes impoverished…’[xi] The

essential point, however, is that the form does not suppress the meaning

entirely, it is still there, albeit at a distance, to be drawn on.

‘The meaning will be for the form like an instantaneous reserve of

history, a tamed richness, which it is possible to call and dismiss in a sort

of rapid alternation: the form must constantly be able to be rooted again in

the meaning and to get there what nature it needs for its nutriment…’[xii]

Thus, in the case

of Malone’s work, putting pre-established fragments of text together with

fragments of imagery is like building a doubly complex myth and creating a

metalinguistic sign from two or more pre-existing signifiers, each of which may

draw on multiple pre-determined meanings. Depending on which features one calls

up, and in which combination, the resulting interpretation might be infinitely

construed – a rich plethora of ambiguity. Barthes concludes:

‘Myth is a pure ideographic system, where the forms are still

motivated by the concept which they represent while not yet, by a long way,

covering the sum of its possibilities for representation.’[xiii]

Since Malone’s

work, like the mythical concept, has at its disposal an unlimited mass of

signifiers (words and images), and since ‘there is no regular ratio between the

volume of the signified and that of the signifier’,[xiv] so

there is no limit on possible routes to and outcomes of interpretation.

Aldrich’s conclusion therefore holds: both form and content (or, in his terms,

medium/materials and content/subject matter) are key to the aesthetic

experience and interpretation, and this, with his rich variety of mixed media,

is an understanding that Malone exploits to the full.

© Anna McNay,

February 2017

Published in the catalogue to accompany Nick Malone: A Tale of Two Lives at Art Bermondsey Project Space, 14-25 March 2017

Also available on Nick Malone’s website

[i] Virgil C Aldrich, Philosophy of Art,

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc, 1963, p92

[ii] Owing to a long-term friendship with the

writer William Empson

[iii] Simon Morley, Writing on the Wall. Word

and Image in Modern Art, London: Thames & Hudson, 2003, p10

[iv] ibid, p17

[v] GE Lessing, Laocöon: An Essay upon the

Limits of Poetry and Painting (1766) (trans with introduction and notes by

Edward Allen McCormick), Baltimore, MD, 1962, p77. Cited in J Dixon Hunt, D

Lomas and M Corris, Art, Word and Image. Two Thousand Years of

Visual/Textual Interaction. London: Reaktion Books, 2010, p15

[vi] Morley (2003), p9

[vii] ibid

[viii] Aldrich (1963, p94) elaborates on this,

using Dylan Thomas’ poem, The Ballad of the Long-Legged Bait, as an

example:

‘Suppose […] you ask […] what does it mean? This could

be taken as a question about content and subject matter […]. But to press the

question in this direction would be to turn your back on what counts perhaps

even more, which is the texture of the medium of the composition; and that is

what a good interpretation […] will draw attention to. How does the interpreter

do this? How does he help you to the aesthetic experience of this property of

the medium? He reminds you of the materials of the poem, not its subject

matter.’

[ix] Roland Barthes, Mythologies,

(selected and translated from the French by Annette Lavers), St Albans: Granada

Publishing Limited, 1973, p120

[x] F de Saussure, Course in General

Linguistics, New York: Philosophical Library, 1959

[xi] ibid, p117

[xii] ibid, p118

[xiii] ibid, p127

[xiv] ibid, p120