19/01/17

Digging into the Quicksands of Time: Jane Walker’s

Divided Cities as a Metaphor for Civilisation’s Lack of Civilisation

‘It has become easier to divide people than to unify

them, and to blind them than to give them vision.’[1]

Throughout

history, nations and cities have been divided. Reasons have been various, but

include race, class, politics and religion. Even today, in the so-called ‘first

world’, cities such as Nicosia and Jerusalem remain riven and Rome has an

independent country – the Vatican City – at its centre. In our contemporary

society, divisions are proliferating – nations are becoming disunited and,

witness the Brexit vote in the UK, unions torn apart.

In her

recent series of paintings, Jane Walker both divides and unites, creating

jigsaw-esque topographies of ‘divided cities’, with stark boundaries, but new

borders: Marseilles meets London; Paris meets New York; travel is both

prohibited yet made conceptually possible.

Walker has

long been painting cities and professes to a strong interest in the English

topographical watercolour tradition. Initially wanting to become a concert

pianist, from the age of seven, and with a brief foray into the study of

medicine, she went on to train at the Royal Academy Schools (1987-90), at first

painting more traditional portraits, but a visit to India led her away from conventional

Western figurative painting. Attracted to ornate Eastern window traceries, her

own work became increasingly linear and decorative. A move to Sheffield 18

years ago then provided Walker with wide-reaching views from her studio,

looking out and down across an ever-changing cityscape. She began to paint what

she saw, but not quite as she saw it…

All

two-dimensional art requires some form of spatial translation, be it through

the use of formal techniques, such as linear perspective, creating illusory

space that makes the viewer ‘see’ three-dimensional depth on a two-dimensional

canvas, or the more contemporary choice of choosing to play with a viewer’s visual

perceptions of the world itself, subverting the figurative or landscape

traditions and questioning the very language of painting. Walker, impressed by

the compressed space in the work of her tutor, Sonia Lawson, sought to escape

the confines of illusionistic space and mimesis. ‘The background space in my

work is deliberately undefined, unanswered,’ she says. While, at first glance, her

works might seem to resonate with modernist and abstract expressionist

paintings – lines of emotion, vivid colours, intertwined and bouncing off one

another, sparking conversations and kindling feelings – a closer look reveals a

depth within her canvases, as well as recognisable figurative elements. Her

artistic trick, then, is to invert what she sees so that the larger buildings

are on top, weighing down on the smaller ones. Taking a slightly bleak, if

realistic, view, Walker sees this as a metaphor for what is happening to cities

today, whereby the pressure of increasing populations, high rents, lack of

space and congestion hangs heavy. Her lines, which, on the surface, seem to

hold things together, are brittle. One worries as to how much more pressure

they can take.

While

Walker’s linear style might be seen as an exploration into post-cubist –

digital even – formal deconstruction of the pictorial space, it is arguably also

an employment of Byzantine – or inverse – perspective. Walker herself describes

‘a move backwards to a fragmented medieval space’. Byzantine perspective – frequently used in the painting

of icons – locates the vanishing point outside of the painting, where the

viewer stands, rather than within the painting, as is the case with linear

perspective. The viewer thus experiences multiple points of perspective, which has been described by the Atelier

Saint-André as ‘allow[ing] the viewer a window into the Kingdom of God’.[2]

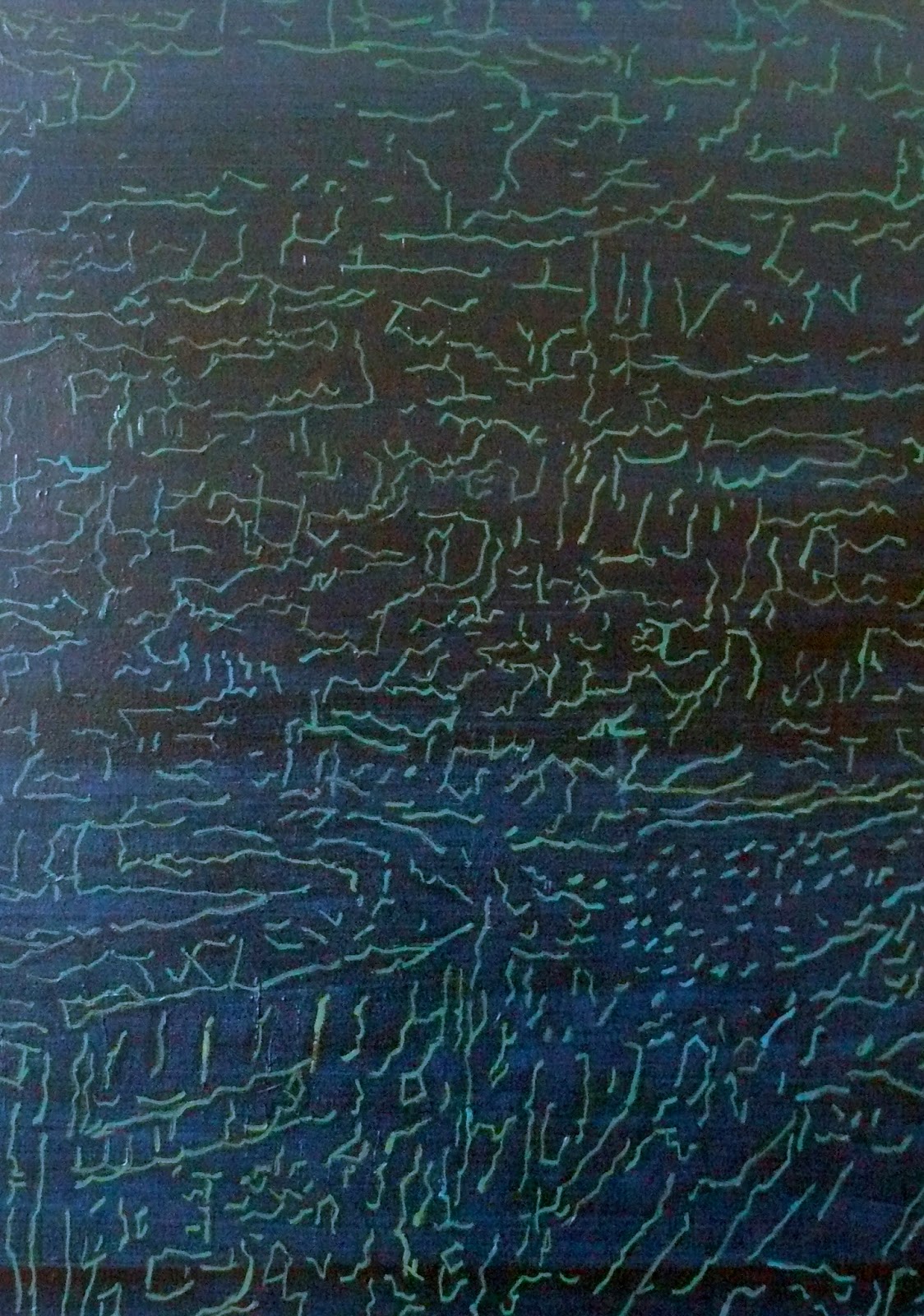

Perhaps not

inappropriately, then, Walker’s paintings also call to mind medieval

illuminated manuscripts. From a distance, the horizontal sequences of marks

might easily be mistaken for lines of Arabic or Hebrew script. Even on knowing

whence the imagery derives, one cannot help but look for hidden meaning in the calligraphy

– this ‘indelible writing on the landscape’. And elements are indeed buried in

these archaeological canvases and panels, for Walker works in layers, building

up and sanding down, creating a palimpsest out of ghostly traces. Between the planes is a pictorial space, different

from the illusion of space suggested by perspective. Aware of this scriptural similarity, Walker

sometimes creates an edge to her composition, like the decorated border of a

manuscript – another demarcation or boundary line, attempting, perhaps, to

restrict the growth of the cities within. Metropolises abound enough.

It was a

friend’s throw-away comment that the line seemed to be the most important

aspect of her work, that led to Walker ridding her practice of nearly all else,

focusing solely on this line – reducing her painting to its drawn – or perhaps

written – essence. For more than a decade, Walker worked in watercolour, her

painting becoming increasingly graphic. She sees her current style as a

distillation of watercolour techniques, transferred to oil paint.

Her process

begins with photographs that she takes from high vantage points – the Natwest

Tower, the Empire State Building, upstairs in her studio – looking down over

cities. She inversely projects these images on to her panels, canvases or papers

and traces the outlines in black, simplifying and subtracting as she goes. She

then builds up layers of wash, in different colours, before painting over the

black lines in white. This, she sees as ‘almost like trying to write across

things’, creating a photographic reversal, transcribing and translating. Layers

are built using primer, often repeating the process – reprojecting, redrawing,

relayering, repriming – to create a mesh of hidden worlds. With her divided

cities, each section is drawn from the projection of a different city,

arbitrarily partitioned, amorphously shaped. Areas are marked out atlas-like,

new boundaries defined with primer. String and cotton are sometimes worked into

the layers, adding further tension and divisions – every strand, every mark,

demarcating, dislocating, dissevering. Vertical clefts appear when the paint

drips downwards, pooling at the bottom, in contrast to the tiny buildings,

collapsing under the increasing weight above them, dissolving into nothing,

sinking into the quicksands of imagination, vision and time.

Colour is

significant to Walker as well. Sometimes she paints ‘stripes’ across her

compositions, dividing the cities still further. Contrarily, the wash on top

softens their outlines, blurring the boundaries beneath. Identifying with the Northern

landscape tradition, in which light is important, yet colour tends to the

monochrome, Walker sees her lines as the encapsulation of light – almost as if

she were drawing with rays, tracing the photograph as if it were itself a

drawing. In between these lines, beneath and above, she uses complex,

contrasting colours, pushing the boundaries in yet another dimension. On the

surface, she often uses silver or gold, to pull out the imagery still further.

Like the Sienese master, Duccio di

Buoninsegna’s, Walker’s linear

and decorative style maintains a lyrical note, with the use of colour creating

pattern and rhythm. Depending on the angle from which you approach one of her

works, the white outlines luminesce and reflect – or perhaps refract –

different colours from their inner rainbows. There is an element of batik, or

of scratching away at the surface to reveal what lies beneath.

Indeed,

Walker describes her work as ‘trying to do something between writing and

image-making’ and as ‘looking down and seeing what we’re going to leave behind’.

The ruins of previous civilisations lie hidden beneath the sand, sometimes

covered over and built upon, before being rediscovered and revealed. This

ongoing process of defining, destroying, disguising and deciphering –

humankind’s action towards its urban habitat – is metaphorically re-enacted in

Walker’s work. Thus, while her compositions, overall, might seem – even seek –

to divide, they most certainly do not

blind. If anything, they open their

viewers’ eyes to a whole new realm of possibilities and understanding, both for

the past, the present and the future. If only civilisation could learn some

civilisation.

[1] Suzy Kassem,

Rise Up and Salute the Sun: The Writings of Suzy

Kassem, Boston: Awakened Press, 2011

[2] www.atelier-st-andre.net

Images © the artist

See more of Jane’s work on her website