30/08/16

Julie Umerle: An

Exploration of Mark-Making

An essay on the occasion of

Julie Umerle: Rewind

AB Project Space

31 August – 10 September 2016

‘First and foremost, “mark” is a product as well as a process,’ writes

Kelly Baum.1 ‘More specifically, it is an end that cannot be

separated from its means.’ Marks may issue directly from the artist’s hand, via

a brush or a palette knife in contact with the canvas, or there may be some

attempt on the part of the artist to hand over control and distance him- or

herself from the process. Even so, the resultant marks are the traces of an artist’s

action. When Jackson Pollock poured his paint directly from the can, or dripped

it from a stick, for example, his direct influence might have become less

apparent, but, nevertheless, it was still his bodily movement that

choreographed the encounter between paint and canvas. Harold Rosenberg spoke of

the abstract expressionists as producing ‘events’ rather than ‘pictures’. ‘The

painter,’ he wrote, ‘no longer approached his easel with an image in his mind;

he went up to it with material in his hand to do something to that other piece

of material in front of him. The image would be the result of this encounter.’2

For Julie Umerle, this assertion might hold in part, but, influenced by

minimalism and post-minimalism as well as the ‘new American painting’, her work

is an exploration of mark-making of many different types.

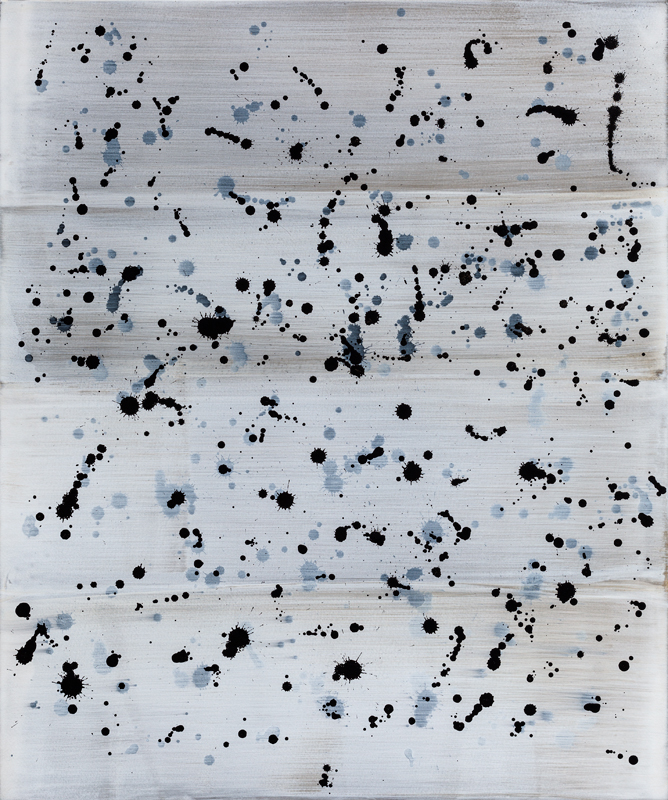

The works closest in spirit to the ‘encounter’ alluded to by Rosenberg

are those in her Transoxide series

(2015-16), built up on wet

stretched paper with a coloured ground, as a successive layering of white paint

and flicked splatters of ink. With the initial colour pulled across the sheet with

a large brush, forming a ‘grid’, the accumulated layers veil this underlying order

with their seemingly haphazard clusters. Suggestive of multiplying cells, reproducing

bacteria, or dark stars in a bright sky, there is an element of the organic,

echoed also by the splitting and cracking of the ink on the surface, varying in

degree according to the specific mixture used in each case.

These paintings are an experiment, both in

mark-making and materials, and typical of the way in which Umerle works:

progressing from one piece to the next, continuing an idea, cycling through open-ended

series, pushing boundaries and exploring elements that fascinate her along the

way. The

physicality of the medium and her attention to surface are countered, however,

by a strong compositional element within the structure of the paintings.

Drift III (2016), for example, is a reworking of an earlier piece that got

damaged. Attempting to recapture what it was she loved about the previous work,

Umerle has, nevertheless, both subtly repositioned the looming black shapes,

and, per force, submitted to the will of gravity and the pull of the paint

itself as it drips down the canvas. Here, as is also the case for Naples Orange (2013) and Buff Titanium (2013), the drips result

directly from the pressure of the brush as it is swept across the softly

coloured, divided ground – an interesting contrast in terms of direct contact

to the remote mark-making of the Transoxide

series’ flicking approach, treading that fine line between directing what you

want the paint to do and letting it do its own thing; between precision and

chance.

The Rewind series (2014-16) sets out to

isolate and refine the marks from the Drift

paintings, positioning them tightly within the square frame of an unprimed

canvas, exploiting the pictorial space to the max. With the omission of the

drips, the process is obliterated, and the mark-making becomes defined instead by

technique. Similarly, the loss of action asserts both the flat forms and the

flatness of the canvas itself. This is, as Charles Harrison termed it,

‘painterliness, freed of depicting function’.3 First in black, and

then, in the later paintings, in red, the series invites the viewer to hit the

pause button and observe in still meditation. With the black shapes, it is like

looking through space, aiming towards infinity, while, in contrast, the red

shapes appear to jump forwards, escaping the pictorial frame and entering the

viewer’s own personal space. As the ‘painter of black’, Pierre Soulages, said:

‘It’s important to experience aesthetic shock, which sets in motion our

imagination, our emotions, our feelings, and our thoughts. That’s the purpose

of a painting and of art in general.’4 Umerle certainly achieves

this, both by her stripping bare of these shapes – revealing the ‘nakedness’

that Robert Motherwell attributed to abstract art – and by the large scale of

many of her works, which seem to shout out to you, compelling you to stop and

look, engaging you in what Mark Rothko described as ‘an immediate transaction’,

drawing you in ‘to create a state of intimacy’.5

Early in her

career, Umerle was advised by Robert Ryman to avoid naming her works after

feelings and, indeed, she describes her feelings as being shut off when she is at

work, as she becomes engrossed in the creative process. Viewers’ responses are

always subjective, and any associations they make, be they figurative or

emotional, are entirely their own. The black Rewind triptych offers something of an enigma code, suggesting an

order in which the hieroglyphs might be read, inviting the viewer to attempt an

interpretation. Take note, however, that, as with the Holy Trinity, each of

these three entities might be more than one thing at once and, overall, no

satisfactory understanding might be attained: it is, perhaps, equally a matter

of submission and belief.

Just as

Motherwell saw his work in terms of ‘a dialectic between the conscious

(straight lines, designed shapes, weighted colours, abstract language) and the

unconscious (soft lines, obscured shapes, automatism)

resolved into a synthesis which differs as a whole from either’6, so

Umerle’s work treads a similar path, proving that formal and spontaneous

procedures are not necessarily incompatible and that mark-making truly is both

a means to an end and an end in itself.

Notes:

1. Kelly Baum, ‘Rothko to

Richter/ Mark-Making in Abstract Painting from the Collection of Preston H.

Haskell, Class of 1960.’ Essay to accompany the exhibition of

the same name at Princeton University Art Museum, 2014. Available online at:

http://artmuseum.princeton.edu/story/rothko-richter-mark-making-abstract-painting-collection-preston-h-haskell-class-1960

[Accessed 18/07/16]

2. Harold Rosenberg, ‘The American Action

Painters’, 1952, reprinted in Ellen G Landau (ed), Reading Abstract Expressionism. Context and Critique, Yale

University Press, 2005, pp189-197, p190

3. Charles Harrison, ‘Abstract Expressionism’

in Tony Richardson & Nikos Stangos (eds), Concepts of Modern Art, Penguin, 1974, pp168-210, p172

4. Zoe Stillpass, interview with Pierre

Soulages in Interview magazine,

published 05/08/14. Available online at:

http://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/pierre-soulages/#_ [Accessed 18/07/16]

5. Mark Rothko, from

excerpts from a lecture given at the Pratt Institute in 1958, noted by Dore

Ashton and published in Cimaise,

December 1958. Cited in Harrison (1974), p195

6. From a statement in Sidney Janis, Abstract and Surrealist Art in America,

New York, 1944, cited in Harrison (1974), p170

Images:

All courtesy the artist

Drift III (2016)

150 x 150cm

acrylic on canvas

Transoxide III (2015)

60 x 50 cm

aquacryl and shellac ink on wet stretched paper

Rewind III (2014)

55 x 55 cm

acrylic on unprimed canvas

Buff Titanium (2013)

135 x 150cm

acrylic on canvas