Bhupen Khakhar: You Can’t Please

All

Tate Modern

1 June – 6 November 2016

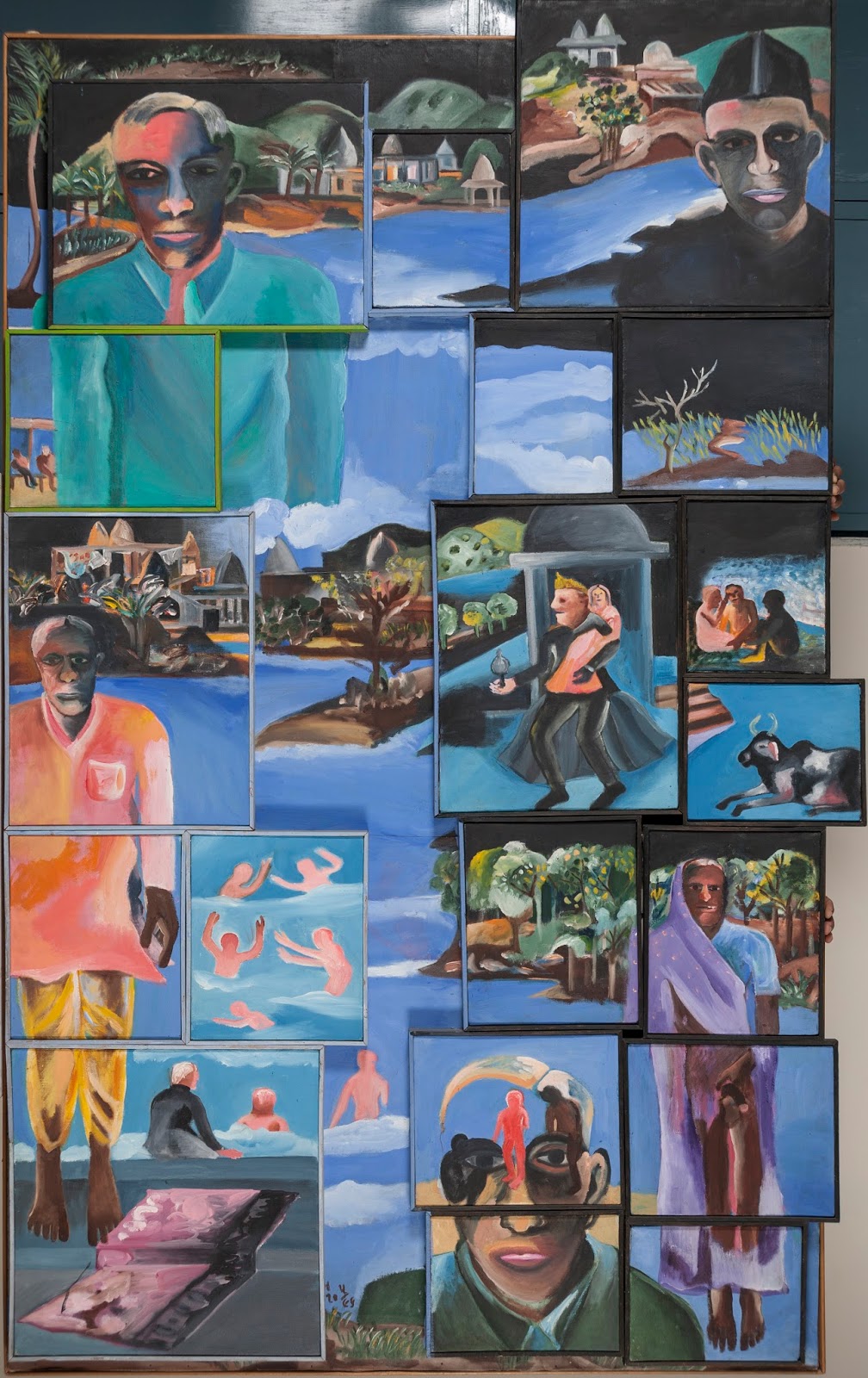

From a distance, the paintings in

this exhibition look like large-scale Indian miniatures, with their vibrant

palette and simplified, flat, illustrative characters. Look more closely,

however, and there are floating figures that could be from Marc Chagall,

foliage that looks like something from Henri Rousseau,

elements of pop art, and then, uniting it all, a devotional style that could be

straight out of 14th-century Sienese painting. This stylistic symphony is

punctuated by a wry humour and narrates contemporary scenes – often multiple scenes per work – of Indian life: the life

of ordinary workers and tradesmen; of the artist and his older, male lovers;

and of the degeneration of his body as he fights, and ultimately loses, his

battle against prostate cancer. Comprising 91 works from across five decades,

this is the first international retrospective of the work of Bhupen Khakhar

(1934-2003) since his death and, according to incoming Tate Modern director

Frances Morris, it is “part of the spirit of the bigger international story

that the new Tate Modern [to be opened to the public on 17 June after its £260m

extension] is dedicated to”.

This political aspect is drawing

the exhibition both praise (for widening the version of art history shown to

the British public) and criticism (for being no more than just a politically

correct gesture and disregarding the quality – or lack of quality – of the

work), and it is true that, with paintings quite this steeped in narrative, the

average visitor to the gallery might find him- or herself struggling to

identify without some prompting as to the sociocultural references at hand.

That said, there is much that can be drawn from the works with just the basic

information provided in the wall texts and, moreover, need one necessarily always

comprehend every last dot and dash in order to enjoy something for its aesthetic

merits? This is perhaps the biggest misconception of people who worry about

going to a gallery because they “don’t know enough” – and it is a shame,

because it is only through looking (and then perhaps reading a little

background or context afterwards), that one learns anything at all. I would

thus urge would-be visitors not to be put off by a lack of familiarity with

Indian culture or history, regardless of what some critics say.

Read the rest of this review here