17/09/15

Interview: Sun Yi

Sun Yi: Sidelines

Presented by ART.ZIP

Candid Arts Trust Gallery

14-20 September 2015

“As a child,

I didn’t understand the definition of being an artist,” says recent Slade

graduate, Sun Yi (born 1988), in his typically philosophical manner. “Sometimes

there are remains from the ancient past and people call these artworks; then,

if they know who made them, these people are called ‘artists’. If I’m a

teacher, I have to go to school to teach every day; if I’m a postman, I have to

ride around the city delivering mail every day – but what do artists do? Someone

might say: ‘I haven’t had any inspiration or made any work for 10 years,’ but

he is still an artist. It’s a different phenomenon. It’s hard to define. These

people do what they like and they write about what they want, so, if that’s an

artist, maybe I am an artist too.”

In his

artist statement, Sun continues: “Art, as far as I have practised it, seems to

me like water, tasteless, but you could never live without it. Whatever forms

it takes, I get bored as the excitement fades and as time passes, I even forget

it ever existed.” What becomes clear, talking to Sun, is that his practice, to

a large extent, is about playfulness and exploration. An idea he reiterates

numerous times throughout our conversation is: “Really, it’s just about being

playful. I don’t like to do things with a purpose.” But what makes a work of

art, I ask? “I had a tutor at the Slade,” Sun recalls, “who always said we

could only do art by making things. In my mind, there are the things I want to

make, and then I make them: so these could be artworks.”

I wonder,

then, what he makes of artists like Duchamp, with his readymades? “Oh, it’s

still making something,” Sun says without hesitation, “because he moves the

object somewhere new. It’s all about an action of the mind or an action of the

body – that’s the practice that declares whether something’s a work or not.

Even a photograph: it’s not by the machine, because you press the button.

That’s the action of your making it.”

When setting

out on a new work, Sun doesn’t have any expectation as to how it will look once

finished. “It’s like an architectural concept that pushes me to make my work,”

he explains. “I don’t know the final result. I don’t mean the kind of

architectural design that’s separate from the actual fabricating of the

building, like we have today, but more in the vein of Antoni Gaudí, who made

the whole building himself. His time was the building’s time. He could change

the work during the process. Architects today can’t do this. In my work, I can

change things during the process. It’s not really necessary to follow any

structure.”

Sun works

with many different media and is continually responding to every day things.

His works aren’t invested with any particular meaning, as he prefers to let

viewers bring along their own interpretations. In addition, meaning doesn’t

come from any one work in isolation; it’s about the exchange of things. In 2014,

Sun put together a performance in Beijing that embodied this idea quite

literally. Called the One Cent project, it comprised Sun inviting audience

members to buy his paintings for one cent a piece. If they didn’t have a one

cent coin, however, but still wanted to buy something, they could exchange

something of theirs, which they deemed appropriate in value. What remained at

the end – Sun’s work, coins and objects exchanged – was documented

photographically. “Again,” Sun says, “it was a playful work. But it asked

people to think about the world we live in and its systems. It was humorous,

but it was also quite political.”

At

university in China, Sun began reading German classical philosophy for

pleasure. “I don’t think it’s exactly necessary knowledge for an artist,” he

says. “It was more of a personal hobby.” But his encounters with Kant and

Wittgenstein gave him a different angle from which to analyse things. “Sometimes

talking about an artwork involves thinking about a particular theory.

Philosophy, art and science – they belong to the same ideology.”

Concepts

play an important role in Sun’s creativity, although he is not sure whether he

would class himself a conceptual artist. “My work depends on a concept and my

work can be a concept too, but I don’t necessarily know what that concept is.

Some concepts are unknown, but they’re still conceptual.” As ever, we teeter on

the brink of some truly epistemological debate. Sun continues by drawing a

distinction between inspiration and ideas. “Inspiration is generated from

somewhere,” he explains, “from nowhere even, but ideas are under the control of

the mind. I can create ideas through drawing. Drawing, for me, is something I

can do everywhere. You have to keep your mind open and accept everything you

possibly can accept, then inspiration will come. The mind is changing all the

time. Memory can create ideas from previous inspiration.” Sun considers drawing

to be his primary medium. “For me, the most comfortable thing is the small

object. I like drawing on paper, small-scale. The area should be no bigger than

the size of your hand. I think this comes from my calligraphy practice,

learning to enjoy your drawing freely, without big movements and without

pressure.”

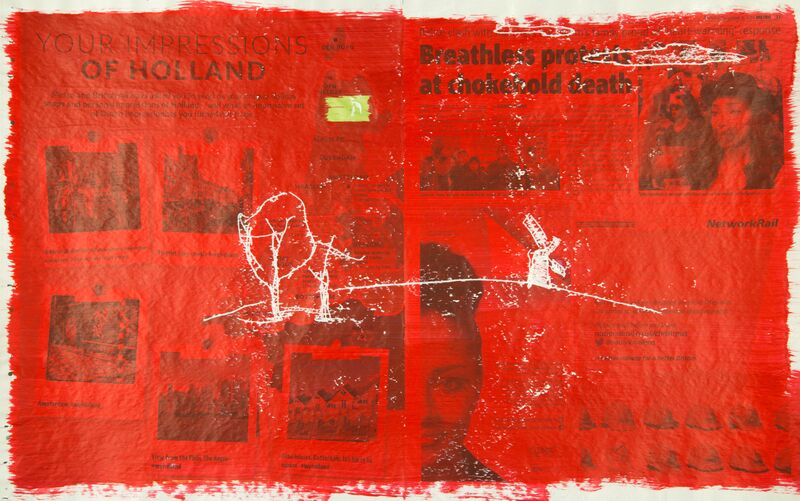

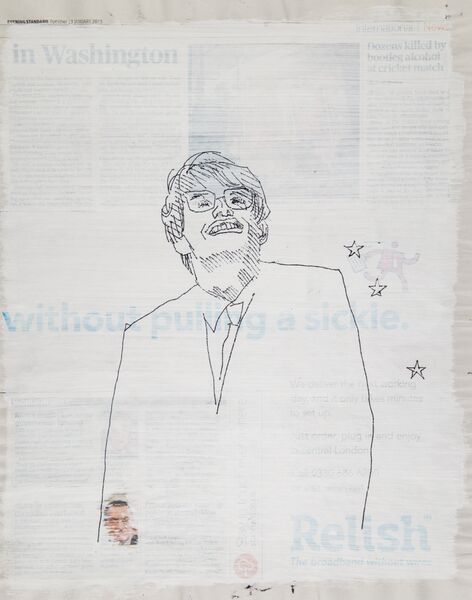

For his suspended

newspaper works, where images are drawn out and (con)texts obliterated, Sun works

on one side of the page, but the work, as he sees it, is on the other side. “That’s

why I display them suspended, so people can see both sides. There are lots of

possible interpretations of the work. For me, it’s about the news, every day

life, the concept of copying, ideologies. But it really doesn’t matter – people

can make their own interpretations. When I started making these works, I had no

reason for using newspapers, in particular – it was just being playful. I have

been asked what I have learnt from using them, but I haven’t got an answer to

that yet. I don’t think I can learn things from art, or my art practice, in the

same way that I can learn a language or learn knowledge. Art is a kind of passive

learning, or a form of experiencing. It’s illumination.”

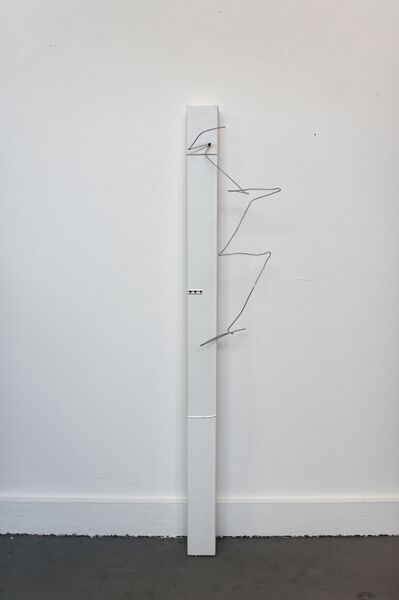

Sun is

currently playing with the concept of 3D drawing, working with found wire, wood

and nails. He sees drawing as much more than just pencil marks on paper. For

example, he considers both Lucio Fontana’s slashed canvases and On Kawara’s

time paintings to be drawings. “Drawing can also be a performance. Bas Jan Ader

went cycling along the canal in Amsterdam and then fell into the river. That is

like a drawing as well. Drawing, for me, is a big concept to develop.” But does

it necessarily involve a line? “Yes. Always. And time.”

Sun grew up

practising calligraphy from the age of five. “I don’t like to call Chinese

calligraphy ‘calligraphy’,” he says, “because the translation is ‘writing

principle’. I prefer to call it this. It’s about line. It can be art, in a way,

but it’s about meaning too. There’s a practical side.” However, he describes

his practice today as being “quite like Chinese calligraphy. We do it again and

again to make it better; we practise it. I think artwork can be done in that

way as well. You can add things or cut things out. Work can be generated at

different times.” He will never make an exact copy of a work, however. He

couldn’t, he says, because time, place and person have all changed. He could

make a newer version, perhaps; something bigger; something brighter. Just not

the same again.

Sun studied

for a BA in Painting at the Faculty of Oriental Art, NanKai University, Tianjin

(2008-12). His was a small, independent department, with a class of just 10

students a year, and there was quite a Western skew to the training, which included

outdoor and life painting, sketching and Western art history, but also

calligraphy. In 2011, he spent six months in Spain as an exchange student and

then he came to London – by way of a language course in Cambridge – to study at

the Slade from 2013-15. London, actually, was Sun’s third choice. Initially he

wanted to go to Paris, but was disappointed by the school, when he went to

visit. Next came Berlin, but the language barrier was a problem. English, Sun

felt, would be easier to master than German. That said – despite his fluent and

very British English – Sun still claims to find the language a struggle. He originally

applied for the MA course at the Slade, but moved to the MFA, as it required

less written work – leaving, of course, beneficially more space for his actual

art practice. Sun nevertheless enjoyed the course’s set reading – and responded

with plenty of writing. “It just wasn’t in English,” he smiles.

Sun is

actually an avid poet. “Our life needs poems, nowadays,” he explains. “Especially

in China. We’re very busy in the city and life is quite tough and relationships

are difficult. We’re losing things from human nature. A poem can be a very pure

sensation. It’s like a reaction to the physical world. It’s a way to express

things. I think the word is much more immediate than the artwork to communicate

what you want to say, but it also can confuse people.”

Later this

autumn, Sun will return to China, before heading stateside to further his

studies. Where exactly, he’s not yet sure, but “somewhere on the East Coast,

possibly New York”. Ultimately, he intends to return to China and establish his

studio there. After his time spent in the West, does his work still have an

Oriental influence to it? “Yes, of course,” Sun replies. “It’s not really

changed a lot since coming to the UK. I can’t change my DNA. Now it’s a

cross-fertilised cultural field – but I can’t give up the Eastern influence.”

Images all © the artist