24/02/15

Chevalier d’Eon: Gender Transgressor

‘It must indeed be acknowledged that she is the most

extraordinary person of the age … we have seen no one who has united so many

military, political, and literary talents.’ [The Annual Register]

Extraordinary as a soldier and diplomat, an author and

spy, and as an expert sword fighter too, the Chevalier d’Eon – Charles

Geneviève Louise Auguste André Timothée d’Eon de Beaumont (1728-1810) – was a

noted figure in international politics and high society. But what made the

Chevalier a truly colourful and celebrated character of 18th century Britain

was the fact that no one was quite sure whether or not s/he was a man or a

woman. Born in France, s/he came to England in 1762, ostensibly as Louis XV’s

interim Ambassador, but in reality also spying for the French King. S/he lived

in London until 1777 as a man, and from 1786 (aged 49) to 1810 as a woman. Rumours

had in fact begun as early as 1771 and bets of more than £200,000 were

regularly placed as to the Chevalier’s ‘true’ sex. Throughout, the Chevalier

remained tight-lipped and would neither speak out on the matter, not allow a

physician’s examination. Ultimately, s/he agreed to the French King’s demands (on

whom s/he was dependent for an income) that s/he should dress ‘gender-appropriately’ –

i.e. in female clothing. The Chevalier continued successfully to fence wearing

a dress – adorned with the Croix de St Louis, a decoration awarded only

to men, and won by d’Eon in his/her time as a Captain in the French Dragoons.

Upon his/her death, d’Eon was found

to be physically typically male. S/he was buried in the churchyard of Old St

Pancras Church, which adjoins the St Pancras Hospital grounds, where Camden

& Islington LGBT History Month’s annual art exhibition, Loudest Whispers,

is currently taking place. This year’s exhibition includes a specially

commissioned work by trans* artist Simon Croft, responding to the life and

legend of the Chevalier. Croft has carefully crafted a chess board – The D’Eon

Gambit (named after the sacrifice of a piece or pieces in order to gain

advantage in the game overall – particularly relevant to the Chevalier’s life,

one might say) – where each playing piece represents a different aspect of the

Chevalier’s life: D’Eon is both the King and Queen symbolising

his/her dual gender presentation and close relationship with the French King; the Knight is represented by

the Croix de St Louis; the Rook

by a sword hilt; the Bishop

by St Pelagius, symbolising D’Eon’s strong religious beliefs and the many

references in his/her autobiography to such gender transgressing religious

figures as precedents for his/her own situation; and the Pawns are represented by the

Burdett-Coutts memorial in St. Pancras Old Church churchyard, where the

Chevalier’s name can be seen second from the top on one of the sides. Despite

using 3D printing techniques, Croft’s playing pieces have remained, almost

contradictorily, relatively 2D. They look both fragile and delicate hanging

above a shattered board. Croft often works with this distinction between 2D and

3D, between concrete identity and variable viewpoints. A 3D object, squashed

flat and restricted to one angle, may then, when hung, as these pieces are, cast

literal shadows of doubt over their superficial appearance.

This is not the only extant artistic representation of the

Chevalier, since there were many contemporaneous portraits and engravings of

him/her fencing in full dress. One notable portrait by Thomas Stewart (1792),

previously mistakenly held to be a portrait of an unknown woman, before being

cleaned and revealing the unmistakable five o’clock shadow, is on display in

the National Portrait Gallery. D’Eon also left behind an autobiography, which

remained unpublished until 2001. Written in French, and very much for a

contemporary public, d’Eon self-refers with a mixture of masculine and feminine

terms. Much of the content can be independently verified, but it is clear that

some stories were invented or altered to suit the self-presentation s/he sought

at different times. In the book, D’Eon presents the life of a female-to-male

transvestite (claiming to have been born a girl and raised a boy), whereas the

truth seems instead to be that s/he was born and raised a boy, later choosing

to live as a woman (thus, a male-to-female transgendered life). What is

apparent is that d’Eon’s life blurred gender binaries and we can only guess at his/her

true sense of gender identity and what that might have meant at the time.

Loudest Whispers 2015

The Art Exhibition of Camden & Islington LGBT

History Month

2 February – 23 April 2015

St. Pancras Hospital Conference Centre

4 St. Pancras Way

London NW1 0PE

https://www.facebook.com/LoudestWhispers

Special Event

Chevalier d’Eon: Gender Transgressor

Friday 27 February

18:00-20:00

Talks by and discussion between installation artist

and transman Simon Croft and LGBT sociologist Natacha Kennedy.

The evening will be hosted by art critic and writer

Anna McNay and includes a new installation based on d’Eon by Simon Croft on

display in the gallery.

Light refreshments provided

For further information: [email protected]

Images:

Simon Croft

The D’Eon Gambit

2014

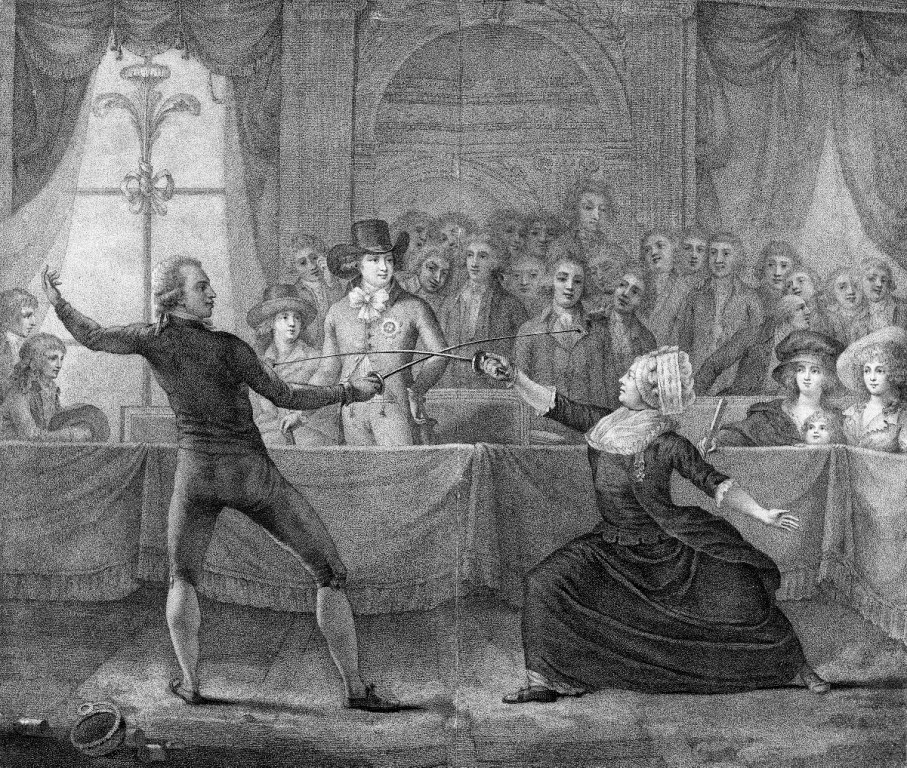

The

Assault, or Fencing Match, which took place at Carlton House on the 9th of

April 1787, between Mademoiselle La Chevalière

D’Eon

de Beaumont and Monsieur de

Saint George.

Engraving

by

Victor Marie Picot, based on the original painting by Charles Jean Robineau

1789

Also published at: http://www.divamag.co.uk/category/arts-entertainment/chevalier-d’eon-gender-transgressor.aspx