07/02/12

Migrations: Journeys into British Art

Tate Britain

31 January – 12 August 2012

The remit for Tate Britain is that its collection should be one of British art. Clearly, however, this is problematic, given not only the state of our multicultural society today, but also the Commonwealth, not to mention the preceding British Empire and beyond that the universally quite peripatetic nature of artists to study, find patronage, escape persecution, and so on. Tate Britain’s latest exhibition, Migrations: Journeys into British Art, largely comprising works from its own collection, takes this conundrum as its starting point, as it seeks both to raise and explore questions about the formation of a national collection of British art against a continually shifting demographic.

The show spans some 500 years, beginning with the influx of painters and sculptors from Northern Europe in the 16th century. Following the Reformation, portraiture became the most acceptable form of painting in Protestant England and Scotland: artists such as the German Hans Holbein (ca. 1497-1543) and the Dutch Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641) were esteemed more highly than British trained artists, and, coming at the bidding of our Royal family, are now known for their iconic images of our kings Henry VIII and Charles I respectively.

A couple of centuries later, however, Britons began to travel abroad, and thus the birth of the 18th century Grand Tour, a critical part of any young gentleman’s education. Ideas were cross-cultivated from the continent, and small memento images were produced by artists such as Canaletto (1697-1768) and brought back as souvenirs. When war prevented Englishmen from travelling abroad in the 1740s, however, Canaletto himself came to London for a nine year stay, and, during this time, he painted a good many English landmarks, including London: The Old Horse Guards from St. James’s Park (ca. 1749), on loan here from the Andrew Lloyd Webber Foundation.

Not long thereafter, in 1768, the Royal Academy was founded in London in order to teach and promote art in England. It is a solidly British institution, yet almost one third of its founding members were migrant artists active in Britain at the time.

Over the coming centuries, dialogues between different nations and artistic styles continued to increase. In the latter half of the 19th century, whilst Paris became acknowledged as the centre for art training, London remained the more stable centre for patronage and commercial artistic success. As such, many British and American artists (including John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) and James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903)) went to train in Paris before settling in London, and numerous French artists, including James Tissot (1836-1902) whose work is included here, crossed the channel both to find work, and also to escape the political aftermath of the Franco-Prussian war. These artists brought with them many new styles and ideas, some more accepted into British society than others. Tissot, for example, despite his attempts to adapt in accordance with British taste, continued to be criticised for his overly frilly and elaborate touches. Whistler, on the other hand, who adopted the Thames as one of his key subjects and produced a great number of Nocturnes, focusing on the atmospheric effects of light on water, was graciously accepted, and remained in London until his death.

The exhibition’s coverage of the 20th century begins with the two quite disparate, but equally influential, Jewish art exhibitions held at the turn of the century: Jewish Art and Antiquities, starring works by William Rothenstein, which argued that Jewish art was essentially just a part of British art, with no independent identity, and The Twentieth Century: A Review of Modern Movements, held at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1914, which, through its attempt to align Jewish art with Modernism, argued for a distinct identity. This section of the exhibition, along with the adjacent works by refugees from Nazi Europe, is indeed a joy to peruse, containing highlights by the likes of Jacob Epstein (1880-1959), David Bomberg (1890-1957), Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980), Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), Naum Gabo (1890-1977) and Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948).

The same might also be said of the works by artists such as F.N. Souza (1924-1959) and Rasheed Araeen (born 1935), which are included in a section on artists who moved to Britain from Commonwealth countries in the 1950s and 60s, but, as the wall texts freely admit, felt, at the time, largely ignored and marginalised by such mainstream galleries as the Tate itself.

The 1960s works range from Gustav Metzger’s (born 1926) auto-destructive art, showcased in the form of a video of the Recreation of First Public Demonstration of Auto-Destructive Art (1965), which restages an event from 1961, whereby Metzger sprayed a nylon canvas, hanging on the Southbank, with acid, so that it slowly decomposed, revealing the vista of St Paul’s Cathedral on the other side, to David Medalla’s (born 1942) conversely auto-creative sculptures, exploring the processes of transformation, and the notion of ephemerality. Certainly, standing watching his bubbles spill out from atop Cloud Canyons No 3: An Ensemble of Bubble Machines (1961, remade 2004), one is transported elsewhere, somewhere high above an earth demarcated by country borders and state lines.

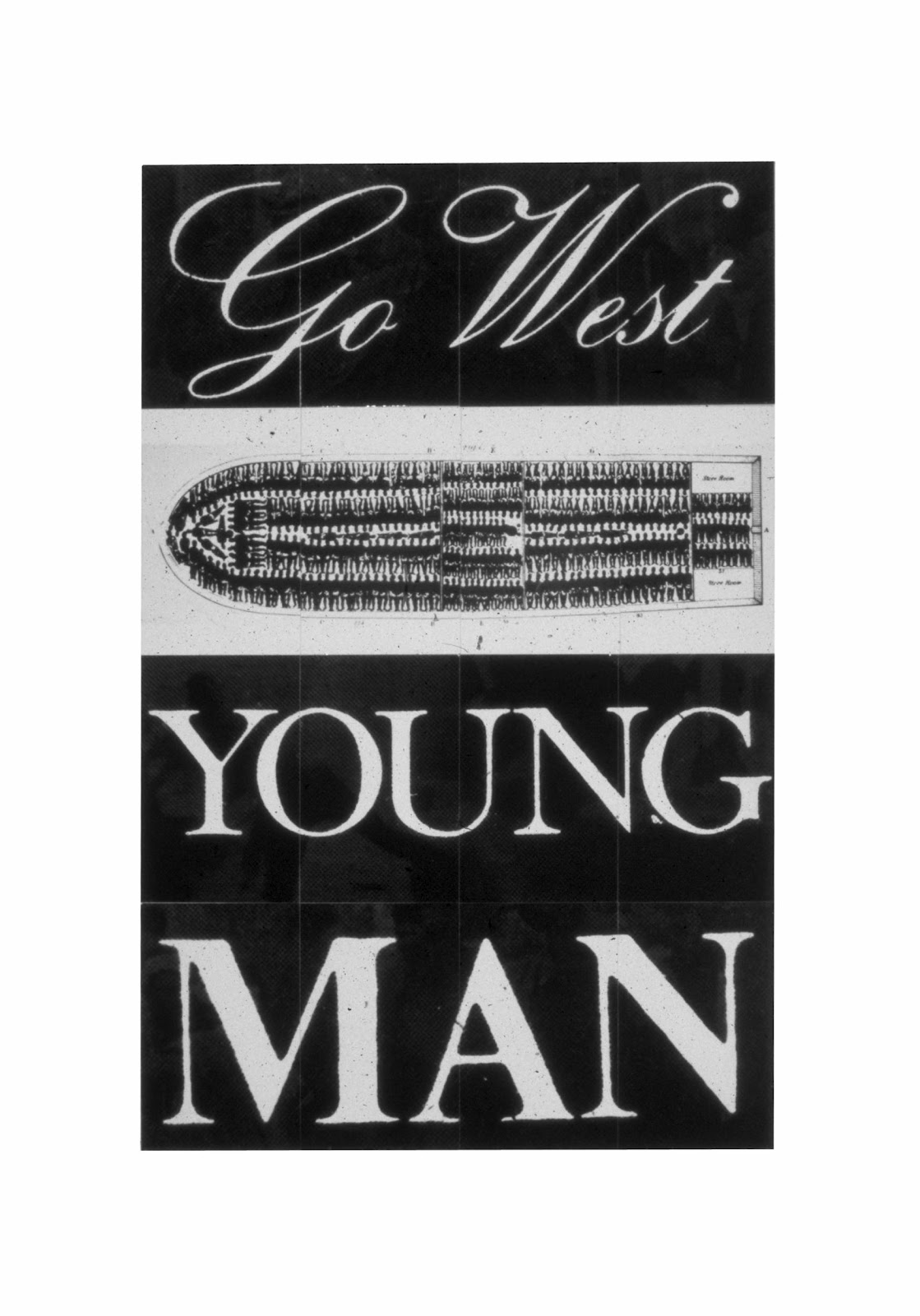

The 1980s are represented largely by works considering the poetics and politics of diaspora and displacement, and the creation of identity in a racist but increasingly migrant-populated Thatcherite Britain. Sonia Boyce (born 1962) considers the identity she is forced to adopt as a black person born and raised in this country, and Keith Piper (born 1960) similarly uses text and photo montage to deconstruct and challenge representations of British history with relation to the African diaspora.

The central part of the exhibition space is taken up by rooms showing video works from the past ten years, supposedly epitomising the very nature of migration, with the moving image itself something transient which does not exist until it find a temporary shelter on a screen. Zineb Sedira’s (born 1962) Floating Coffins (2009) is a 14 screen installation, filmed in the harbour city of Nouadhibou, Mauritania, home to the world’s largest ship graveyard, but also the departure point for West African immigrants hoping to reach the Canary Islands. Using the sea as a metaphor, and with shots of circling migrating birds, questions of belonging and displacement, beginnings and endings, are brought to the fore.

The show’s curators – and there are number of them, each working on their own specialisms – have each, in their own section, put on a good display, and, indeed, questions are raised about how, or even whether, one ought to consider Britishness in relation to art. Nevertheless, the aspiration to keep the rooms open and flowing fluidly one to the next, so that the works can speak to one another across both time and space, is, perhaps, a little too ambitious, and, overall, there is very little coherence between the vast variety of works on display. As an open house exhibition, showcasing some of the Tate’s best acquisitions, it is certainly worth a visit, but don’t necessarily expect to come away with a neatly bound narrative. That said, isn’t the need for this just a pitfall of the tightly curated contemporary art exhibition world in which we now live, where everything is parcelled, explained, and offered to the viewer on a plate? Maybe being left to wander through 500 years of art, drawing your own conclusions about the developments, cross-fertilisations, and impacts of political and social change, is not such a bad thing after all?

Images:

Canaletto

London- The Old Horse Guards from St James’s Park

c.1749

Tate

Lent by The Andrew Lloyd Webber Foundation

James Tissot

Portsmouth Dockyard

c.1877

© Tate

Jacob Kramer

Jews at Prayer

1919

Tate

© Estate of John David Roberts

By courtesy of the William Roberts Society

Photo: Tate Photography

Keith Piper

Go West Young Man

1987

Tate

© Keith Piper

Francis Alys

Railings

2004

Tate

© Francis Alÿs

Photo: Tate Photography