16/11/11

Building the Revolution: Soviet Art and Architecture 1915-1935

The Sackler Wing Galleries

Royal Academy of Arts

29 October 2011 – 22 January 2012

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, a new Marxist-Socialist state was founded under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924). With this came a brief but intense period of architectural design and construction, largely associated with the artistic ideals of the contemporary Constructivist art movement, and with the aim of breaking free from past imperial and bourgeois associations. State headquarters, radio towers, factories, social clubs, schools, colleges, and housing – the scope was broad, and the new style, governed by the principle that function should dictate external form, wholly reflected the ethos and optimism of the new state.

The Royal Academy’s latest offering, Building the Revolution: Soviet Art and Architecture 1915-1935, explores the synergy of the art and architecture of this period, juxtaposing vintage archival photographs of the most significant buildings with corresponding images taken by British-born photographer Richard Pare, who, over the past two decades, has collected nearly 15,000 negatives, reflecting both the architects’ intentions at the time, as well as the present day melancholy of the rapid state of deterioration of many of the structures. In amongst these photographic works are a selection of paintings and sketches, on loan from the Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki, by avant-garde artists including Kazimir Malevich, Vladimir Tatlin, Liubov Popova and El Lissitsky.

The exhibition opens with the first industrial structure to be built after the Revolution, Vladimir Shukhov’s Shabolovka Radio Tower, erected in 1922 for the newly established propaganda broadcasters, Comintern. Inspired by Vladimir Tatlin’s proposed Monument to the Third International (1919-20), the tower was originally intended to dwarf even the Eiffel Tower with a height of 350m. Unfortunately, as with many of these projects, it had to be cut back, due to the limited availability of steel. Nevertheless, at 150m tall, this tower has become one of the most recognisable emblems of Socialist progress. Monument to the Third International, or Tatlin’s tower, as it came to be known, was, on the other hand, never built at all – at least, not in Russia. Back in 1971, a 1 in 40 scale wooden model was commissioned by the Hayward Gallery as part of the exhibition, Art in Revolution. Now, the same architect, Sir Jeremy Dixon, has returned and recreated a steel version for the RA’s Annenberg Courtyard – a symbol, as he puts it, of the Socialist regime’s optimism, which, in its attempt to “achieve the impossible […] absolutely captures the spirit of that moment.”[1]

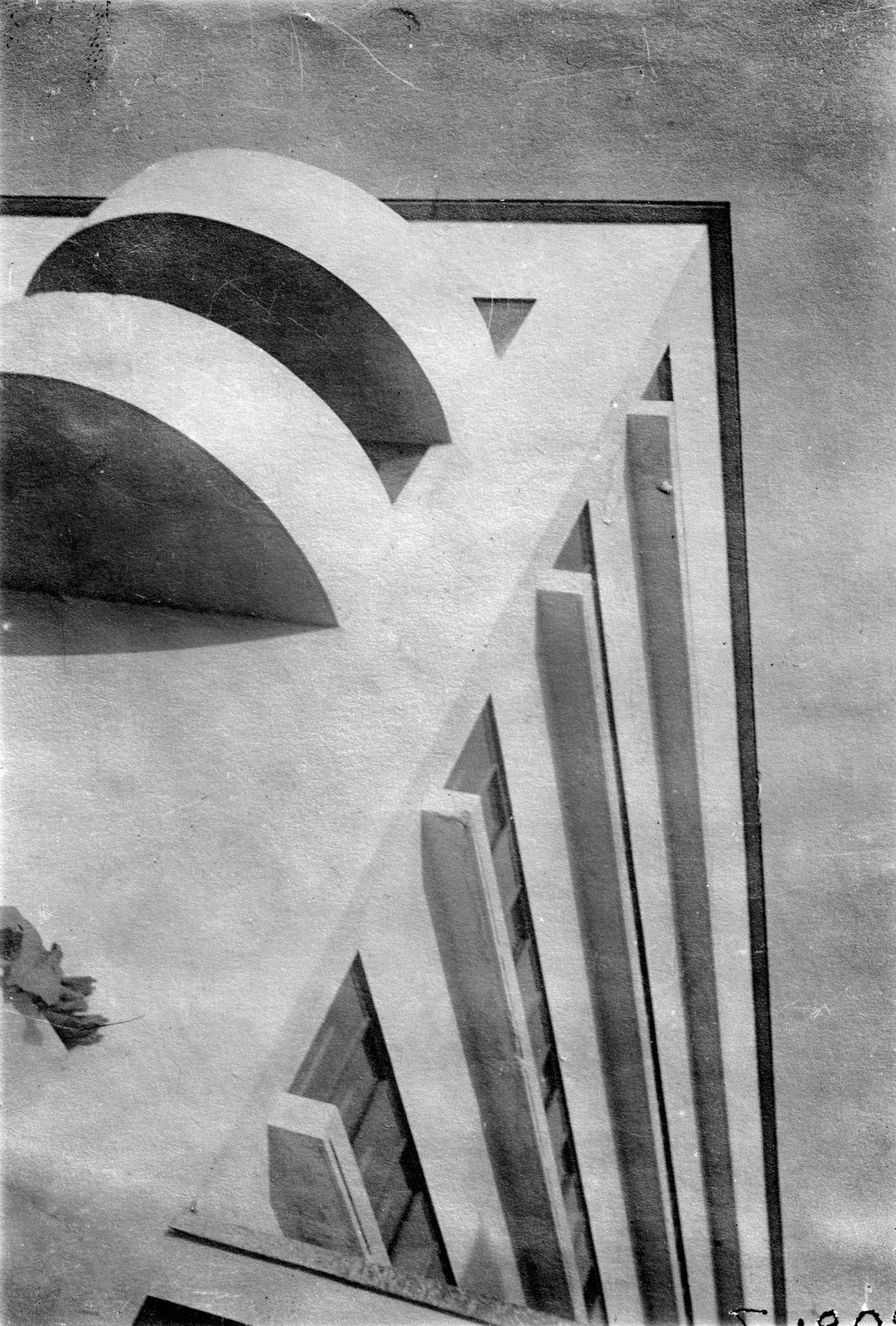

The New Economic Policy of the 1920s saw rapid industrialisation, which brought with it an exodus from rural areas to the towns and cities of the newly formed USSR. This, in turn, necessitated a whole new provision of, predominantly communal, housing. Moisei Ginzburg’s Narkomfin Communal House (1930) is a beautiful example of sleek white forms and flat roofs, whilst the family house designed by Konstantin Melnikov (1931) demonstrates both a geometrically patterned hexagonal fenestration, as well as a more basic grid formation, epitomised also in the Rusakov and Zuev Workers’ Clubs, centres for collective life and the realisation of Socialist values. These structures themselves compare directly with the intersecting forms in Liubov Popova’s Spatial Force Construction (1920-21) and her two Painterly Architectonics (1915-16 and 1918-19 respectively).

The exhibition concludes with a room dedicated to Lenin’s mausoleum. After his death on 24 January 1924, a quick and temporary wooden structure was erected, designed by Alexei Shchusev. This was replaced by a more elaborate structure in the August of the same year, but, as the cult of Lenin grew, a permanent stone-clad mausoleum was commissioned. Finished in October 1930, and highly polished in dark red granite, marble, porphyry and labradorite, this impressive geometric structure was the last of its kind, marking the end of an era. The new Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin (1878-1953), completely rejected all forms of abstraction, passing an edict to permit only Classical architecture, and ordering a return to representational art.

Pare’s own journey to complete his archive is a story in itself. Permitted just 30 minutes to enter the mausoleum with enough light to take his photograph, he was uncertain that his exposure would be long enough to come out with anything respectable. Busying himself with setting up another shot, so as to distract the guards from the fact that he was leaving the film to expose for a little longer than allowed, he could do nothing more than cross his fingers until he got home. Luckily for him, and us, the result was spectacular. Taking us on a journey from start to finish, this comprehensive exhibition thus offers an unparalleled opportunity to witness the development and cross-fertilisation of art and architecture during one of the most exceptional periods of the past century. Even without any knowledge of the historico-political situation, it might be enjoyed as a celebration of pure geometric form – the square, the circle, the line; intersecting planes; rough texture and the mere suggestion of volume. Simplicity, style, and function, both on paper and in 3D.

[1] “Architect’s ‘recreation’ of Russian artist Vladimir Tatlin’s 1,200ft would-be monument takes pride of place at Royal Academy exhibition” by Andrew Johnson, Islington Tribune, 4 November 2011. Accessed from http://www.islingtontribune.com/news/2011/nov/architect’s-‘recreation’-russian-artist-vladimir-tatlin’s-1200ft-would-be-monument-tak on 16 November 2011.

Reconstruction of Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International, known as ‘Tatlin’s Tower’, specially commissioned from Jeremy Dixon of Dixon Jones Architects, in the Royal Academy’s Annenberg Courtyard

15 November 2011

Photograph: Robin Beckham

Richard PareShabolovka Radio Tower(1998)

M.A. Ilyin

Richard Pare